Stress and distress in dementia pathway

This guideline provides advice on the management of stress and distress symptoms in dementia for in NHS Highland (excluding Argyll and Bute).

Careful and detailed history must be taken from patient. Patients with dementia are often not able to give an accurate history therefore collateral history from those who know the patient well is essential.

Full physical examination and relevant investigations should be done.

Consider delirium if there is evidence of disturbed consciousness, cognitive function or perception, which has an acute onset and fluctuating course. Refer to SIGN guideline 157 and/or the Scottish Delirium Association Pathway (see resources)

Identify and treat any other underlying medical problems that may be causative or contributing to distressed behaviour including but not limited to:

|

Constipation |

Refer to: management of constipation in older adult inpatients: Constipation (Guidelines) |

|

Pain |

|

|

Contribution of prescribed and non-prescribed medication |

|

|

Possible sources of infection |

|

|

Urinary retention |

|

|

Dehydration/nutrition |

|

|

Check skin |

Check pressure areas. Is there dry skin or skin condition causing itch? |

|

Electrolyte disturbance, hypo/hyperglycaemia |

|

|

Hypoxia |

Consider infection/cardiac failure/review target O2 parameter |

|

Alcohol use/alcohol withdrawal |

|

|

Carefully assess for symptoms of pre-existing conditions and optimise symptom control where possible |

|

|

For those who are also diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease |

|

|

Any other physical health trigger |

|

If unresolved after addressing modifiable factors, consider watchful waiting in mild/moderate symptoms of stress and distress.

NICE guideline 97 (see resources) states that reasons for distressed behaviour must be explored prior to commencing any treatment for distressed behaviour in people with dementia. It also highlights that staff working with people with dementia are appropriately trained in the management of distressed behaviour.

NHS Highland have been delivering NES Stress and Distress training to staff working in care homes and across the wider older adult mental health service. The recently developed Stress and Distress Team is based in New Craigs and can assist with the non-pharmacological management of distressed behaviour across NHS Highland through providing psychological interventions for managing distress in dementia.

NHS Highland offer two S&D training programmes both of which map onto the NES Promoting Excellence Framework (see resources).

Staff can access training by contacting: nhsh.stressanddistress@nhs.scot

Stress and Distress Team

Drumossie Unit

New Craigs Hospital

Inverness

IV3 8NP

Tel: 01463 253639

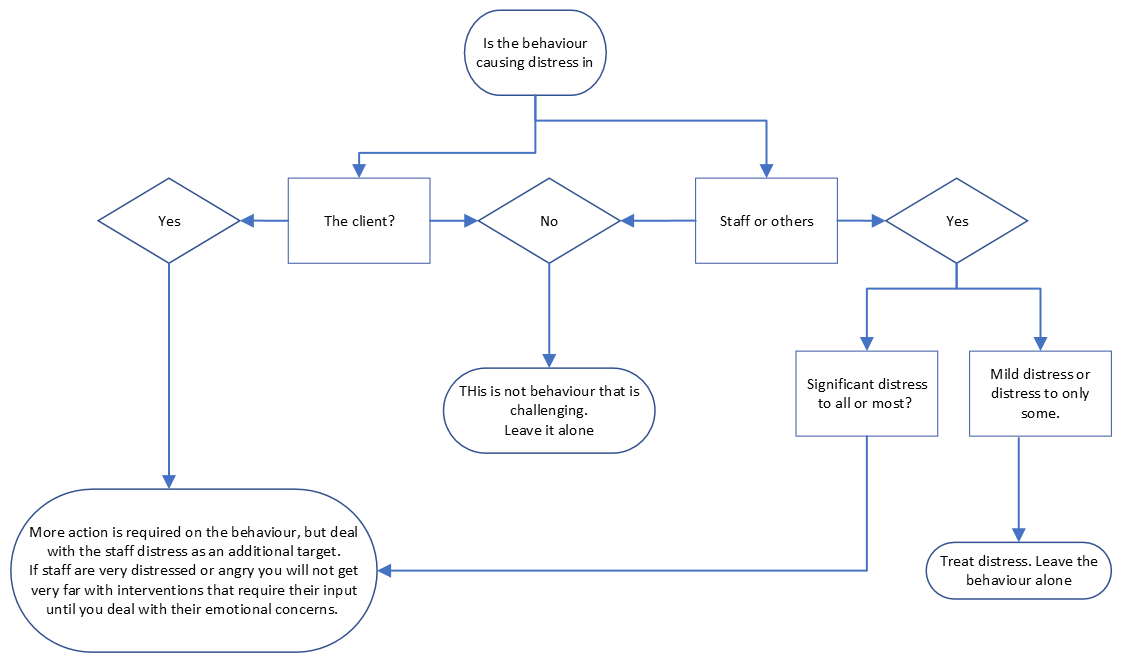

Consider who is distressed and where to focus treatment. This Decision Tree (Bird et al 2012) is to help identify who is distressed (staff distress or patient distress) and therefore where to target treatment.

Pharmacological management of such symptoms can be difficult due to lack of data from robust studies and potential for serious adverse reactions linked to many agents.

Given the significant risks and modest benefits of medication in the treatment of stress and distress behaviours, non-pharmacological interventions detailed above should always be considered first line. Where medication is unavoidable, it should be prescribed in addition to non-pharmacological approaches and not alone.

Patients may be reluctant to take medication or may have swallowing difficulties. If swallowing is a problem consider SALT referral and/or changing medication to liquid or orodispersible.

Reducing the number of tablets, where possible, can help concordance. If refusal is a problem consider utilising different staff members. Spending some 1:1 time gaining rapport before offering medication can help.

For patients who lack capacity and consistently refuse medication, careful consideration could be given to using covert medication. This must only be done with the appropriate legal safeguards in place and documented reviews should occur regularly. The Mental Welfare Commission good practice guide for covert medication must be followed and the care plan (page 17, Appendix 1) completed and discussed with pharmacy and welfare attorney/guardian or carer/next of kin (see resources).

All prescribing decisions should be discussed with the patient if they retain capacity and consent obtained. For patients who lack capacity, where possible decisions should still be discussed and their views taking into account but consent must be sought from their welfare attorney or guardian if one has been appointed. For those who lack capacity and no welfare attorney/guardian has been appointment then treatment decisions should be discussed with the patient and with the main carer or next of kin and their views taken into consideration.

For patients who lack capacity the principles of the Adults With Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 must be followed (see resources). A section 47 certificate and treatment plan must be completed.

|

Target Symptom |

Dementia subtype: Alzheimer’s dementia |

Dementia subtype: Dementia with Lewy Bodies/ Parkinson’s Dementia |

Dementia subtype: Vascular Dementia |

Dementia subtype: Frontal Temporal Dementia |

|

Moderate to severe depression |

Optimise AChEI |

AChEIs not recommended |

||

|

Consider antidepressant (evidence weak)

|

Consider antidepressant (evidence weak) SSRI or trazodone |

|||

|

Anxiety |

Consider regular paracetamol even in the absence of overt pain |

|||

|

Optimise AChEI |

AChEIs not recommended |

|||

|

Consider antidepressant (evidence weak)

|

Consider antidepressant (evidence weak) SSRI or trazodone |

|||

|

Agitation |

Consider regular paracetamol even in the absence of overt pain |

|||

|

Commence/optimise memantine |

Memantine not recommended |

|||

|

Consider antidepressant (evidence weak) 1st line: sertraline |

||||

|

Consider benzodiazepines for short periods 1st line: lorazepam |

||||

|

Aggression/ severe agitation causing significant distress or risk of harm to patient or others AND/OR Psychosis (hallucinations/ |

Consider regular paracetamol even in the absence of overt pain If situation high risk or antipsychotic continued for >6 weeks seek specialist advice. |

|||

|

Commence/optimise memantine |

1st line AChEIs |

AChEIs and memantine not recommended |

||

|

Optimise/commence memantine |

||||

|

Antipsychotics 1st Line: Risperidone |

Antipsychotics not recommended (but see guidance) |

Antipsychotics 1st Line: Risperidone Note: use with caution high risk of antipsychotic associated cerebrovascular events |

Antipsychotics 1st Line: Risperidone |

|

|

Consider benzodiazepines for short periods |

||||

|

Severe behavioural disturbance posing an immediate risk to self or others |

See 'Rapid tranquilisation guideline' on TAM (see resources). |

|||

|

Other |

For other symptoms, such as sexual disinhibition, please seek specialist review. Drugs to reduce sex drive mustnot be prescribed without a second opinion from the mental welfare commission. |

|||

AChEI = acetylcholine esterase inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Prescribing information on each of the drugs is available from the:

It is the prescribing clinician’s responsibility to make sure they prescribe according to the most up to date information available, particularly noting the adverse effects, contra-indications and cautions. This is guidance only and the information should be used in conjunction with the clinician’s judgement.

For use in cognitive symptoms refer to the information for 'Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in dementia' on TAM (see resources).

Cognitive enhancers are not recommended in vascular dementia or frontal temporal dementia.

| Cognitive enhancer | Suggested effective dose/range | Cautions/adverse effects to note |

| Donepezil | 5 to 10mg daily |

Bradycardia

|

| Rivastigmine | 3 to 6mg twice daily OR 9.5mg/24 hr patch | |

| Galantamine | 16 to 24mg MR daily OR 8 to 12mg twice daily | |

| Memantine | 20mg daily usual treatment dose (minimum effective dose unclear) |

*please refer to the information sources noted above for detailed prescribing information.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

The available evidence does not support use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in clinically relevant agitation in Alzheimer’s/mixed dementia (including an Alzheimer’s pathology) but they may improve other symptoms of stress and distress (apathy, anxiety, dysphoria, depression) and their use for cognitive symptoms should be optimised to prevent associated distress. Do not stop acetylcholinesterase inhibitors unless there is clear evidence they have caused the stress or distress or an adverse effect and, if planning to stop, withdraw gradually where possible.

There is some evidence to support the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in a range of stress and distress symptoms in dementia with lewy bodies, including hallucinations.

Memantine

The evidence best supports use in agitation, aggression and delusions in Alzheimer’s/mixed dementia (including an Alzheimer’s pathology) but negative trials have also been published. Memantine should be considered in moderate disease and offered in late disease to prevent deterioration in cognitive function and distress associated with this. Do not stop memantine unless there is clear evidence it has caused the stress and distress symptoms or other adverse effect.

There is an inconsistent body of evidence supporting the use of memantine for symptoms of stress and distress in dementia with lewy bodies, dose should be optimised to reduce stress associated with cognitive decline.

It may be appropriate to consider a short course of antipsychotic in delirium. See SIGN guideline 57: Risk reduction and management of delirium and/or the Scottish Delirium Association Pathway (see resources).

Antipsychotic treatment may be effective for psychosis and persistent physical aggression/severe agitation in the context of dementia.

Atypical antipsychotics have the strongest evidence base in aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s Dementia, although benefits are modest. Any potential benefit must be balanced against the risk of adverse events including increased mortality. Other risks include hip fracture, cerebrovascular events, chest infection, worsening cognition, parkinsonism, falls, postural hypotension, constipation, DVT/PE.

A helpful tool for patients/carers is the NICE patient decision making guide: antipsychotic medicines for treatment of agitation, aggression and distress in people living with dementia (see patient information resources).

Useful information leaflets can be accessed from Choice and medication NHS24 (see patient information resources).

Choice and commencement

Risperidone is the only antipsychotic licensed for use in dementia (other than haloperidol, which is not routinely recommended) and should be considered first line unless contraindicated. It is licensed for the short-term (up to 6 weeks) treatment of persistent aggression in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s Dementia unresponsive to non-pharmacological approaches and when there is risk of harm to self or others. The BNF dose is 250micrograms twice daily increased according to response. A lower starting dose of 250micrograms daily should be considered and may be adequate. Maximum dose is 1mg twice daily but the optimum dose is likely lower.

Consider other antipsychotics (used off-license) if risperidone is not tolerated or contraindicated; olanzapine may be considered 2nd line but make choice based on individual patient factors such as previous response or co-morbidities.

Seek specialist advice before prescribing antipsychotics in patients with Lewy Body Dementia or Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease due to their propensity to cause severe adverse drug reactions and significant increase in mortality. A cautious trial of quetiapine (off-license) may be considered after optimising AChEI and considering memantine but supporting evidence is weak.

Start any antipsychotic at a low dose and titrate carefully. Encourage adequate hydration and mobility.

For the use of antipsychotics in rapid tranquilisation see the NHSH Rapid Tranquilisation Guideline available on TAM (see resources).

Antipsychotics in dementia

|

Antipsychotic |

Suggested dose range for use in dementia |

Suggested regime for reduction/ discontinuation in dementia

|

Cautions/ adverse effects to note |

|

Risperidone |

0.25 to 2mg/day |

Reduce by 0.25 to 0.5mg every 1 to 2 weeks |

|

|

Olanzapine |

2.5 to 10mg/day |

Reduce by 2.5mg every 1 to 2 weeks |

|

|

Quetiapine |

12.5mg to 300mg/day |

For doses 12.5 to 100mg daily: reduce by 12.5 to 25mg every 1 to 2 weeks For doses 100 to 300mg daily: reduce by 25 to 50mg every 1 to 2 weeks |

|

|

Aripiprazole |

2.5 to 10mg/day |

Reduce by 2.5 to 5mg every 1 to 2 weeks |

*please refer to the information sources noted above for detailed prescribing information.

Review and discontinuation

Identify and document clear target symptoms. In-patients review at least weekly. For patients in the community review 1 to 2 weeks for side effects and at 4 to 6 weeks for response. Monitor for common adverse effects such as EPSE, antimuscarinic effects, eg, constipation, effects on BP. After a period of consistent resolution of symptoms, or no evidence of a clinically significant response, consider slow discontinuation.

Where appropriate and practical ECGs should be completed at baseline and thereafter where indicated. For in-patients NEWS should be completed as per hospital policy.

If antipsychotics are prescribed for greater than 6 weeks or are continued on discharge from hospital, please inform liaison psychiatry (for in-patients) or sector older adult psychiatric team so follow-up can be arranged. Antipsychotics in dementia should be reviewed at minimum interval of 3 monthly.

The available evidence does not provide strong support for the use of antidepressants for treating depression in dementia therefore they should only be considered in moderate to severe illness. Evidence does not support a particular class of antidepressant; mirtazapine or an SSRI eg sertraline could be considered (SSRI or trazodone for frontotemporal dementia – see below).

There are a lack of trials investigating antidepressants for anxiety in dementia and therefore a lack of supporting evidence. Clinical experience suggests it may be a strategy worth exploring.

The available evidence is mixed but suggests that antidepressants may have a role in treating agitation in dementia. Citalopram has the greatest evidence base but due to its cardiovascular safety profile and contraindication with other QTc prolonging medication it is not generally recommended. Clinical experience suggests a trial of an alternative SSRI e.g. sertraline may be justified (SSRI or trazodone for frontotemporal dementia – see below).

There is some weak evidence to support use of trazodone in stress and distress in frontotemporal dementia.

Fluoxetine has a long half life and may be useful for avoiding antidepressant withdrawal symptoms in those who occasionally refuse medication.

There is evidence for an interaction between risperidone and SSRIs, in particular the increased risperidone concentrations seen with fluoxetine and paroxetine appear to be clinically important. If either of these SSRIs are given to a patient taking risperidone, concurrent use should be closely monitored and the risperidone dose reduced accordingly; a one-third reduction has been suggested with fluoxetine.

Tricyclic antidepressants should be avoided due to their unfavourable side effect profile. Citalopram/escitalopram are contraindicated with any other medications that prolong QTc and for this reason are best avoided.

Antidepressants in dementia

|

Anti-depressant |

Suggested dose range for use in dementia |

Cautions/adverse effects to note |

|

Sertraline |

25 to 150mg daily |

|

|

Fluoxetine |

20mg daily |

|

|

Mirtazapine |

15 to 45mg night |

|

|

Trazodone |

Depression: 100 to 200mg daily |

*please refer to the information sources noted above for detailed prescribing information.

Evidence comparing benzodiazepines with placebo in the treatment of stress and distress is limited and there is no evidence for long term use. Given the significant risk of adverse events such as cognitive decline, increased frequency of falls and hip fracture they are not recommended as general management. They may be considered for short term management of severe acute distress. Lorazepam 500 microgram as required up to 2mg/24 hours may be considered first line due to quick onset of action (30 to 45 minutes) and short half-life.

The prescribing clinician must consider how benzodiazepines will be discontinued and ensure regular review.

For use in rapid tranquilisation please see the NHSH Rapid Tranquilisation Guideline available on TAM (see resources).