Even the most experienced and skilled practitioner will encounter complications. Do not feel alone if, despite your best efforts, a complication still occurs. Discuss any difficulties you encounter with a senior colleague.

Avoidance

The aetiology of complications is multifactorial: patient, operator and procedural factors all have a role to play. Whilst some might consider the commoner complications not to be significant, your professional duty is to carry out all aspects of your duties in such a way that risk of complications is minimised. Putting aside the medicolegal viewpoint, from a humanitarian point of view, childbirth should be a happy and rewarding time. We must try to avoid blighting the experience, or the memory of it.

To try and minimise risk of complications when performing an epidural block, consider the following:

- Is there a good indication for epidural block?

- Are there any contraindications (see Section 1.2)?

- Are there any patient factors, which might increase the risk of complications, e.g. obesity, previous back surgery?

- Has an adequate explanation been given, in light of the above, to the woman and her partner?

- Is the positioning optimal? The importance of this cannot be overemphasised.

- When attempting to identify the epidural space, you must at all times have a mental picture of the position of the end of the Tuohy needle.

- When using a midline approach, it is important to stay in the midline! Continually re-orientate yourself: after administering local anaesthetic, after draping, and after attaching the loss-of-resistance syringe.

- Start with the needle perpendicular to the skin, bearing in mind that slight cephalad angling of the needle may be needed.

- If the catheter cannot be advanced at all beyond the end of the epidural needle, the epidural space has probably not been reached. Never force it.

- Never pull the catheter back through the needle whilst it is still in the patient.

- If pain or resistance to advancement of the catheter is felt, this may indicate impingement of the catheter upon a nerve root or an epidural blood vessel. Provided an adequate length of catheter is within the epidural space, no attempt to advance the catheter further should be made.

- It is unnecessary to leave more than 4-5 cm of catheter in the epidural space unless the patient is obese. Leaving more increases the chance of obtaining a patchy/unilateral block.

- Secure the catheter carefully in place once bleeding from the puncture site has stopped.

- Give all doses incrementally, and assess their effect properly.

- If you are in any difficulty, call for advice/help, whatever the time.

Disorders of coagulation & epidural analgesia/anaesthesia

Coagulopathy due to disease

Specific disorders (eg. factor deficiency or liver disease) should be managed according to the underlying pathology and in conjunction with the appropriate specialists.

Hypertensive disease of pregnancy

- check INR & APTR if platelet count is < 100 x 109/l

- do platelet count pre-epidural

- if trends suggest rapid change, repeat immediately before epidural placement

- platelet count of > 100 x 109/l is considered safe to proceed with epidural

- platelet count of > 80 x 109/l may be appropriate after discussion with the consultant on call.

Thrombocytopenia

- may be gestational, immune (ITP) or thrombotic (TTP)

- trends in platelet count are more important than absolute values

- there is no defined safe ‘cut-off’ for the platelet count

- discuss with a senior colleague, if in doubt.

Anticoagulant treatment

- full anticoagulation is a contraindication to regional analgesia/anaesthesia.

- avoid regional anaesthesia/epidural catheter removal for

- 4 hours after unfractionated heparin,

- 12 hours after a prophylactic dose of low molecular weight (LMWH) heparin, and

- 24 hours after a therapeutic dose.

- avoid giving unfractionated heparin until 2 hours and LMWH for 4 hours after regional block

- low dose aspirin therapy is considered to be of minimal risk.

Generally, central neural block/epidural catheter removal is considered safe if

- INR is <, or equal to, 1.5

- APTR is <, or equal to, 1.5

- platelet count > 80 x 109/l

Symptoms and signs of excessive bruising/bleeding, e.g. under the blood pressure cuff, should be sought, as they may signify increased risk of bleeding irrespective of test results.

Remember adequate coagulation is a function of quantity and quality, and simple tests of coagulation do not give highly discriminatory information. Thus, if in doubt, discuss with a senior colleague.

Also bear in mind that any stated limits are arbitrary and relative risks and benefits must be considered for all patients.

If epidural warranted in presence of borderline situation/results

- the most skilled anaesthetist available should perform the block

- if suitable, a spinal may be preferable to an epidural

- avoid NSAIDs if coagulopathic

- monitor postpartum for signs of epidural haematoma and investigate any neurological problem as an emergency.

Bloody tap

Cannulation of an epidural blood vessel, thought to be less likely to occur if

- paramedian (vs. midline) approach is used

- 5 to 10 mls of fluid is injected prior to catheter insertion

- a smaller needle is used

- the needle/catheter is not advanced into the epidural space during a contraction when the epidural veins are further engorged

Bloody tap with the needle

- diagnosis obvious

- remove needle and reinsert at a different interspace

- if blood is obtained again it may be a new vascular puncture or from the first.

Bloody tap with the catheter

- diagnosis is made on aspiration of blood, although this is not always the case (pain may be felt)

- withdraw the catheter in 0.5 cm increments, flushing with saline until aspiration of blood is no longer possible

- if insufficient catheter (< 2 cm) is left in epidural space or unsure about blood on aspiration despite withdrawing catheter, remove catheter and re-site epidural

Positive intravenous test dose

- Inadvertent intravenous injection of local anaesthetic despite gentle aspiration with 2 ml syringe prior to test dose

- not easily detected unless adrenaline containing local anaesthetic used with continuous ECG monitoring – not available on SJH Labour Suite, so it is essential to advise the patients about symptoms and to report tinnitus, oral paraesthesia or palpitations

- The catheter must be removed and resited (cannot be withdrawn as above).

Gestational thrombocytopenia and indications for platelet counts in labour

Thrombocytopenia is usually defined as a platelet count under 150 × 109/L; this value represents the 2.5th percentile of the distribution in a healthy population of men and non-pregnant women.

The 2.5th percentile for the platelet count at the end of pregnancy (116 × 109/L) is significantly lower than the value accepted in the general population. This 2.5th percentile is similar for pregnant women of all nationalities or races; Europeans (North, South & Eastern), Asians, Africans, N.America & S.America. Less than 1% of normal pregnancies have a platelet count of <100 x 109/l.

It is a commonly held belief (Bromage) that epidural / spinal block is safe with platelet count > 100 x 109/l. because as a (poor) predictor of surgical bleeding the bleeding time does not become prolonged until platelet count is < 100 x 109/l.

Gestational thrombocytopenia is common and thought to be due to hemodilution and or increased platelet turnover:

(Rolbin USA)

0.4% healthy pregnant women - platelet count < 100 x 109/l

6.4% - .. .. < 150 x 109/l

(Burrows USA)

8.4% healthy women in labour - platelet count 100 – 150 x 109/l

In Europeans, a similar prevalence of gestational thrombocytopenia exists (5.9% Finland, 10.9% Switzerland).

Population studies in healthy, normotensive pregnant women have repeatedly showed platelet count pre-pregnancy and in first trimester is normal, it falls through pregnancy with a nadir at 32-36 weeks gestation and then normalises at day 3-5 post-partum. The PT & APTT and bleeding time are normal.

Hence in normal pregnancy (normotension and without proteinuria) in normal, asymptomatic women i.e. no history of easy bruising, recurrent epistaxis or prolonged bleeding after simple cuts or operations, not taking drugs or herbs nor suffering from a medical condition associated with a coagulation or haemostatic deficit a platelet count is not routinely indicated prior to performing epidural or spinal anaesthesia. There is a concern that ITP may be missed. This is unlikely, however, as all pregnant women attending for antenatal care get a full blood count performed at the booking clinic in the first trimester and again in the second trimester. Possible ITP would be noted from these tests.

In the @ 0.4% normal pregnancies where the platelet count is < 100 x 109/l it would be reasonable to perform a platelet count, PT & APPT prior to performing an epidural or spinal. Finally, for those women who have not had routine antenatal blood tests performed, a platelet count prior to regional analgesia is indicated.

Gestational thrombocytopenia is not considered below a threshold of 75 × 109/L, where the diagnosis of HELLP, ITP, sepsis (chorio-amnionitis), auto-immune disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) should be considered.

In the group of women with thrombocytopenia between 75 and 115 × 109/L, @ 75% have HELLP or pre-eclampsia. In this group, there will be a clinical history and supportive BP recordings and urine proteinuria to confirm the diagnosis. Also consider HIV and Hepatitis C in women with similar level of thrombocytopenia but without proteinuria and hypertension.

In pregnant women with a platelet count less than 75 × 109/L, further investigations are essential. (PT, APTT, LFT’s, U&E’s)

Indications for platelet count & coagulation screen in labour

- History of congenital or acquired bleeding disorder

- Conditions assoc. with haemostatic dysfunction i.e. renal, hepatic, auto-immune disease

- Acute peri-partum conditions:

- PIH or pre-eclampsia (BP 140/90 mmHg and proteinuria 2+)

- HELLP

- Placental abruption

- Amniotic fluid embolism

- Massive haemorrhage

- Sepsis

- Intrauterine fetal demise (risk increases from time of fetal demise)

- Monitor anti-coagulant therapy

- Monitor coagulation therapy e.g. Platelet transfusion in ITP, Clotting factor replacement in haemophilia, Von Willebrand’s disease

- No antenatal care.

In many of the above it is clear that coagulation tests are indicated and neuraxial blockade contraindicated anyway.

The incidence of spinal or epidural haematoma is rare @ 1/150,000 and is invariably associated with a coagulopathy i.e. PT, APTT are prolonged and other indices of coagulation are deranged (e.g. increased FDP, fibrinogen, D-dimer). There is also a cause for the coagulopathy. Concomitant use of drugs affecting coagulation (warfarin, heparin or LMWH) and old age are other associated factors.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Commonly presents in young women - 1/1,700 prevalence in pregnancy. Differentiating these from normal pregnancy with low platelet count is the problem as @ 66% ITP are mild and asymptomatic during pregnancy. Pointers are a low platelet count pre-pregnancy and 1st trimester of pregnancy (75-100 x 109/l). Symptoms when present range from simple bruising, purpura, through epistaxis to GI bleeding. Possible family history of ITP or other auto-immune disease esp. SLE may be found. Individual platelet function maybe normal or increased. Platelet count tends to fall further during pregnancy. Case reports of inadvertent or deliberate but uncomplicated epidural or spinal injections in patients with platelet counts < 20,000 x 109/l. exist.

Dr S Rowbottom

May 2005

(updated Dr P Purvis 2022)

References

- Rolbin SH. et al. Epidural anaesthesia in pregnant patients with low platelet counts. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:918-920

- Burrows RF. N Eng J Med 1988:319(3);142-5. (July 21)

- Sainios S. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:744-9

- Boehlen F. Obstet Gynecol. 2000:95;29-33

- Bromage PR. Neurological complications of regional anaesthesia for obstetrics. In Shnider SM. Anaesthesia for Obstetrics.

- Burrows RF, Kelton JG. Fetal thrombocytopenia and its relation to maternal thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1463–6.

- Boehlen F, Hohlfeld P, Extermann P, de Moerloose P. Maternal antiplatelet antibodies in predicting the risk of neonatal thrombocytopenia. Obstet Gynecol 1999;93:169–73.

Inadvertent dural puncture

Once the diagnosis has been made, it is important that successful analgesia is achieved. There are two alternative strategies:

1) Re-site the epidural in an adjacent (cranial) space

This can be done by yourself if you are sufficiently confident, or by a more senior anaesthetist. Don’t be surprised or worried if your confidence falters after doing an inadvertent dural tap.

Be cautious with the first dose of local anaesthetic through the catheter as the tip may lie near the puncture site. All doses should be fractionated and given over 3 to 5 minutes.

2) Continuous subarachnoid block

This must be discussed with a senior colleague.

Catheter (preferably end hole) is passed into the subarachnoid space. 2 cm only should be left in the space. The catheter must be clearly marked as being subarachnoid’ or ‘spinal’.

1 ml initially, then 0.5 ml increments, of the standard solution (0.1% levobupivacaine with 2 mcg/ml fentanyl) can be used to establish analgesia and for subsequent top-ups. Doses should be given with the patient in the lateral or supine wedged position. All doses must be given by an anaesthetist.

It is important to appreciate that levobupivacaine is slightly hypobaric thus sudden movement risks unpredictable displacement in the CSF, and sitting up may result in an unexpectedly high block.

For LSCS, manual removal and rotational forceps delivery, with the patient in the lateral or wedged supine position, give 0.5 ml increments of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine until adequate anaesthesia is achieved. A maximum dose of 4 mls should be given as caudal pooling of solutions containing dextrose has been associated with development of cauda equina syndrome.

For lift out forceps, positioning as above, give 1 to 2 mls of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine.

General points

Once analgesia is established a full explanation should be given to the patient, her partner and the midwife looking after her. The obstetric team should be informed.

Elective forceps delivery is no longer considered essential but having allowed adequate descent of the presenting part, excessive pushing/straining should be avoided. Obviously, definition of excessive is an obstetric clinical judgement.

After delivery, the mother should be allowed to mobilise freely. Restricting her to bed rest will not prevent PDPH.

Events must be clearly documented in the notes and the patient visited daily until she is discharged. She should be given labour ward contact details, a letter for her GP and a RCOA ‘Headache post epidural’ information sheet (available in the labour ward anaesthetic room). The on-call consultant should be informed.

Post dural puncture headache (PDPH)

70 - 90% of women who have an inadvertent dural puncture with a 16G Tuohy needle will develop a PDPH. The incidence is < 1% with specially designed spinal needles. Parturients are more susceptible to PDPH than the general population. Symptoms usually start within 48 hours of the dural puncture and last approximately 10 days, but may last weeks, months or rarely years.

The pathophysiology is not entirely clear, but PDPH is thought to occur when leak of CSF leads to contraction of the subarachnoid space and compensatory expansion of pain sensitive intracerebral veins, cranial nerve roots and/or meninges.

Typically the mother has a severe, disabling fronto-occipital headache, which is relieved by lying down and worsened by standing or sitting up. The headache may radiate to the neck/shoulders and be associated with other symptoms such as nausea, visual disturbances and even photophobia. If the patient sits up and upper abdominal pressure is applied the headache will often temporarily improve, supporting the diagnosis.

The symptoms are distressing and usually prevent the mother from being able to care properly for her newborn child. Immobility increases the risk of thromboembolic disease and infection, and discharge from hospital is usually delayed. More severe complications such as cranial nerve palsies, subdural or intracranial haemorrhage can occur, but are thankfully very rare.

A full history and neurological examination should be performed. The following alternative differential diagnoses should be considered and excluded:

- simple headache or migraine

- meningitis (septic or aseptic)

- preeclampsia

- electrolyte disturbance or hypoglycaemia

- raised intracranial pressure

- central venous sinus thrombosis.

Conservative management:

- simple analgesics (paracetamol & nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories)

- avoid dehydration

- avoid constipation (may need lactulose).

- caffeine – 300mg in 24h

Dehydration can exacerbate PDPH so should be avoided. Overhydration does not prevent PDPH.

Other measures such as sumatriptan and sphenopalatine ganglion block have been used but there is no strong evidence for their efficacy. As such, their use in our unit is not routine.

If the PDPH does not resolve within 24 hours with conservative management an epidural blood patch should be discussed and offered.

Epidural blood patch (EBP)

This is the definitive treatment for PDPH occurring following inadvertent or deliberate dural puncture. The reason or way it works is unclear, although it is thought to relate to effects on cerebrospinal haemodynamics.

Prophylactic (ie postpartum, just before removal of epidural catheter) blood patching has been used but there is no evidence to support its use.

EBP should be performed after full explanation to the mother and full discussion with the consultant on for labour ward. A consent form should be signed by the clinician and the patient.

Ensure the patient is apyrexial and that other causes for severe headache have been excluded.

Ensure also that the patient has not received LMWH within 12 hours.

Contraindications are as for other central neuraxial procedures (see Section 1.2).

Side effects include failure, inadvertent dural puncture, back pain, transient nerve root pain and pyrexia.

EBP is effective in > 70%; headache may recur in up to 50% of mothers necessitating a further blood patch. When successful, relief is usually immediate.

Procedure

This requires two operators using aseptic techniques.

One operator sites the epidural needle in the epidural space at, or just below the level of the puncture.

The second takes 20 mls of autologous blood from the patient under sterile conditions.

The blood is injected slowly via the Tuohy needle into the epidural space, stopping if the mother complains of pain in her back or legs (a sense of ‘fullness’ is often expressed).

2 mls of saline should be used to flush the epidural needle as it is withdrawn so that a plug of blood is not left.

The mother should lie flat for 2 hours then be encouraged to mobilise normally.

Hypotension

It is uncommon to get significant hypotension from a correctly managed epidural block for labour. The possibility of aortocaval compression, inadvertent subarachnoid or subdural block should be considered.

If however, the blood pressure falls (< 100 mmHg or > 30 % fall from pre-block mean arterial pressure) move the mother into a full lateral position. Infusion of a small volume (100 mls) of crystalloid and increments of 3mg ephedrine or 20mcg phenylephrine should be given intravenously to restore normotension. Pre-filled syringes of ephedrine are kept on the epidural trolley.

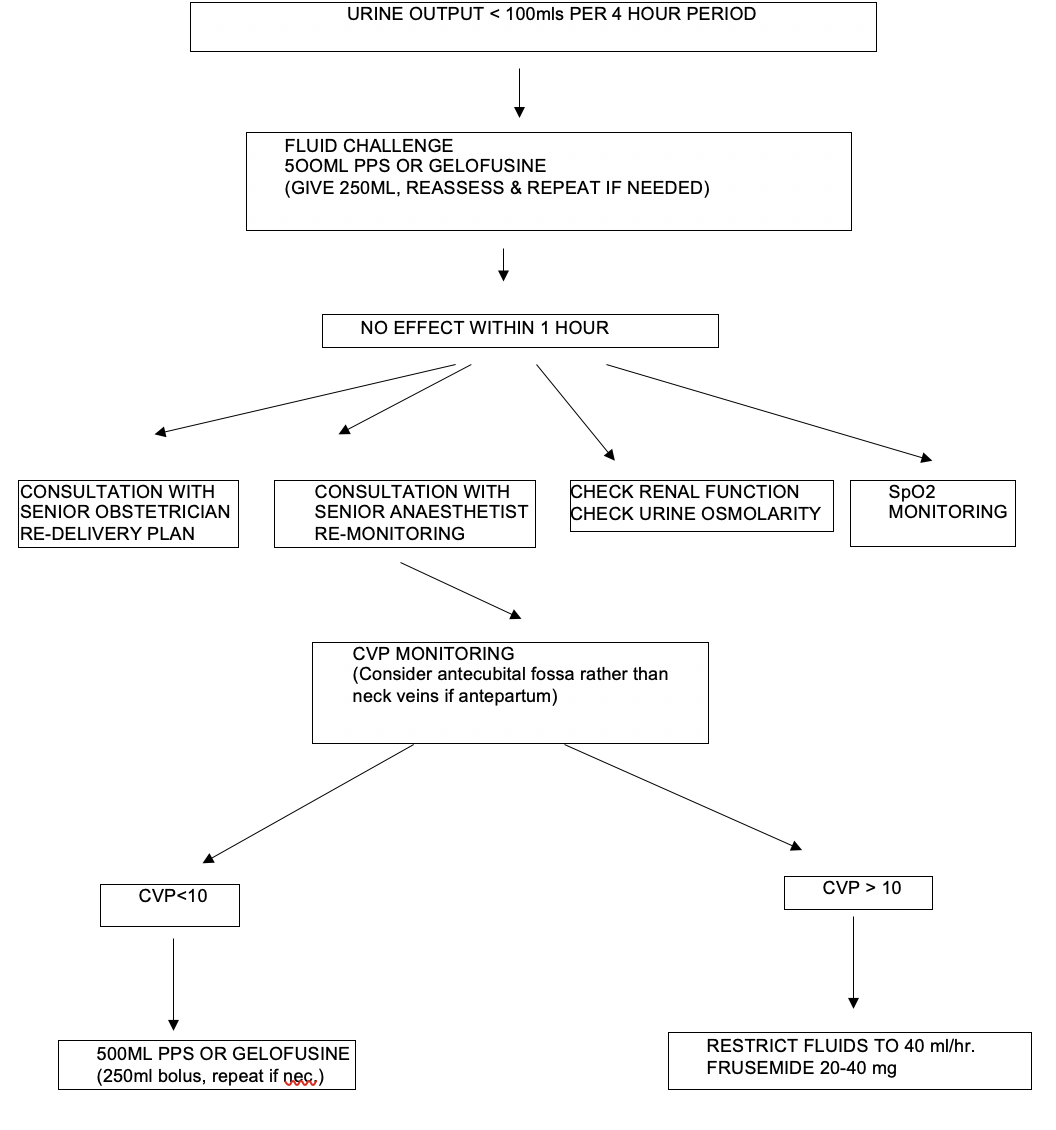

Beware of giving large volumes of crystalloid to women in labour, particularly if labour is being augmented with syntocinon; syntocinon has an antidiuretic effect and the combined result may be water intoxication, hyponatraemia and convulsions. A careful record of fluid balance should be kept through labour.

Pruritus

More common with neuraxial than systemic opioids and in pregnant versus non-pregnant women (probably effect of oestrogen on opioid receptors). Severe in < 1%. Mechanism not entirely clear. Incidence is highest with morphine and lowest with the more lipophilic drugs eg fentanyl.

If the patient is distressed and treatment is needed, the following can be tried:

- simple antihistamines

- naloxone bolus (40 mcg iv increments)

- naloxone infusion (0.4 – 0.6 mg/h)

- other treatments such as propofol, ondansetron, nalbuphine & promethazine have not been formally evaluated.

High block & inadvertent (total) spinal

A high block can be defined as spread of a block three or more segments higher than anticipated.

A total spinal can be defined as a block that results in loss of consciousness and severe cardiorespiratory compromise.

May be due to inadvertent subarachnoid (> 1: 5,000 - 50,000) or subdural (up to 1: 100 obstetric epidurals) administration of local anaesthetic or just unpredictable spread.

Careful epidural administration of fractionated doses of local anaesthetic should help identify an inadvertent spinal and avoid precipitous changes in block height.

Subdural blocks are characterised by slow onset (approximately 20 minutes) of a high but patchy sensory block, often with poor analgesia and usually with little motor block or hypotension. The epidural catheter should be removed and the epidural resited.

For high block (> T4) with cardiorespiratory compromise but no loss of consciousness:

- call for help if you need it

- place in full left lateral position

- give oxygen via a facemask (> 10 l/min)

- give 3 -6 mg boluses of ephedrine or 20-40mcg of phenylephrine

- atropine 600mcg or glycopyrollate 200mcg likely to be required if cardio-accelerator fibres involved (T1-T4)

- give 500 ml bolus of fluid

- reassure mother and her partner

- observe mother and foetus closely.

For total spinal as described above:

- call for senior anaesthetic and obstetric assistance (2222, state “Obstetric Emergency” and location)

- place in full left lateral position

- give 100% oxygen with bag & mask if apnoeic

- give 500 – 1000 ml IV fluid rapidly

- give 15 mg ephedrine IV and repeat as necessary

- Intubate if unconscious & apnoeic

- put full monitoring on

- consider using other vasopressors (eg phenylephrine in 50 - 100 mcg increments or even adrenaline in 5 – 10 mcg increments if hypotension resistant)

- consider emptying stomach with an orogastric tube

- monitor fetus and consider delivery once mother stabilised.

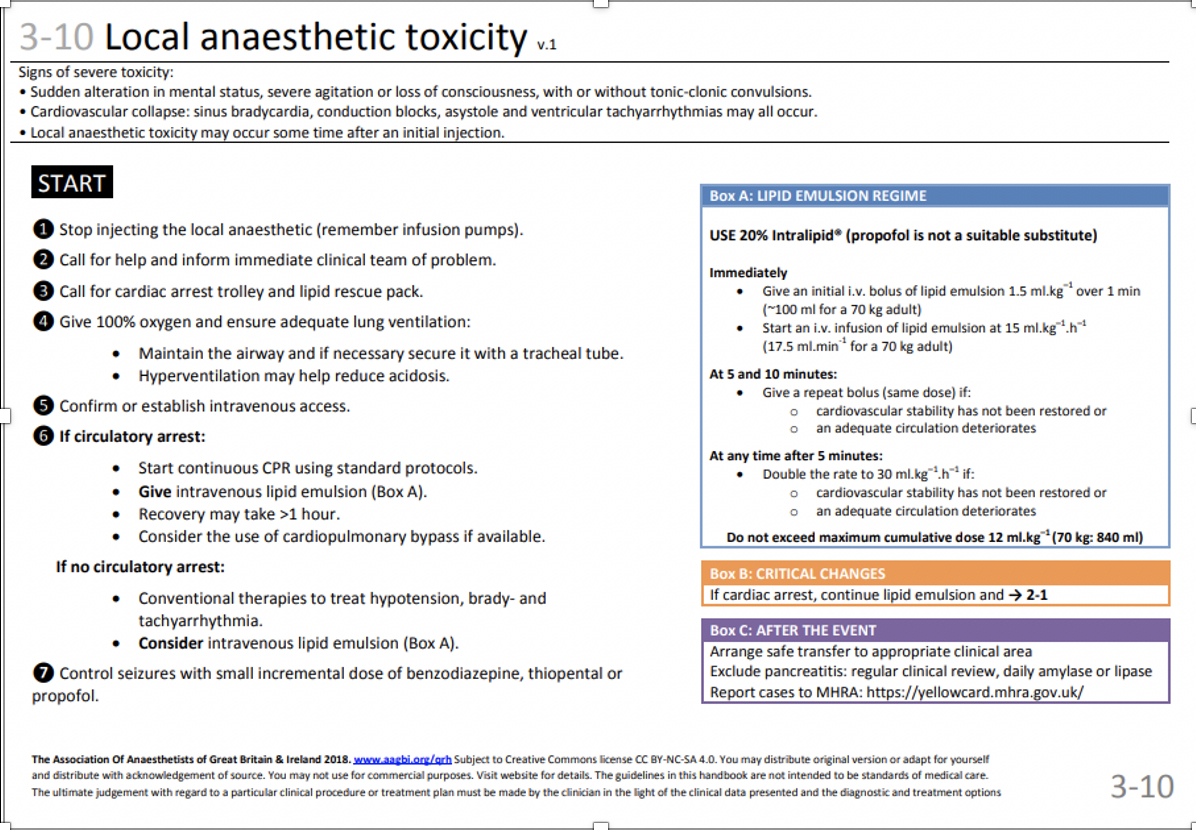

Local anaesthetic (LA) toxicity

This may manifest itself with predominant central nervous system (CNS) or cardiovascular (CVS) effects. Of the agents most commonly used on labour ward, the former is more commonly seen with lidocaine, and the latter with bupivacaine.

CNS irritability resulting in convulsions may progress to CNS depression; CVS collapse can lead to cardiac arrest.

Symptoms and signs may include: tinnitus, light-headedness, visual disturbances, circumoral numbness, drowsiness, convulsions, apnoea, hypotension, ECG changes (P-R interval, A-V dissociation, QRS), sinus bradycardia and asystole.

Newer agents (ropivacaine & levobupivacaine) seem to have a wider safety margin compared with bupivacaine, which behaves in a particularly cardiotoxic way in pregnant women.

LA toxicity in this setting usually occurs where excessive doses of LA have been used (epidural administration), or where inadvertent intravenous injection has occurred.

The following dose limits should not be exceeded:

Bupivacaine/Levobupivacaine 2 mg/kg

Lidocaine 3 mg/kg without adrenaline

7 mg/kg with adrenaline

All doses should be fractionated and given only after careful aspiration.

If suspected LA toxicity occurs:

- stop giving LA

- call for help (anaesthetic & obstetric)

- ABC pattern of resuscitation (NB remember tilt/wedge to avoid aortocaval compression)

- treat convulsions with diazepam (5 -10 mg IV) or thiopentone (50 mg increments)

- consider giving intralipid. This is stored in the labour ward theatre cupboard next to the local anaesthetic agents. It is also kept in the arrest trolleys, both in labour suite and main theatre recovery. See page 57 for recommended treatment regime.

- The LA toxicity guideline in the Association of Anaesthetists Quick Reference Handbook can also be used.

Problems on post-natal follow-up

The anaesthetic team on labour ward is responsible for post-natal follow-up of all women who have had a peripartum anaesthetic procedure. Usually the consultant does the visits, but trainees are also expected to do them, particularly at the weekend, unless exceptionally busy.

The post-natal visit serves several purposes:

- prompt detection of complications of anaesthetic procedures

- opportunity to discuss experience (particularly if unpleasant)

- collection of audit data.

In addition to questions regarding efficacy of and satisfaction with, analgesia /anaesthesia, information regarding the following should be sought:

- neurological symptoms & signs (including bladder/bowel sensation & function)

- pain control

- nausea/vomiting

- pruritis

- backache

If in doubt, take a full history, perform an examination and discuss the patient with the on-call anaesthetic consultant covering the unit.

These mothers must contact one of the obstetric anaesthetic consultants (via the community midwife) if the headache recurs or there are any other adverse neurological symptoms.