Prolonged seizure / status epilepticus in adults (Secondary Care) (Guidelines)

What's new / Latest updates

25/04/24:

- Wording amended as there is no longer a requirement for Pabrinex to be given before glucose. If hypoglycaemic, glucose is to be administered immediately.

10/06/22: Guideline updated

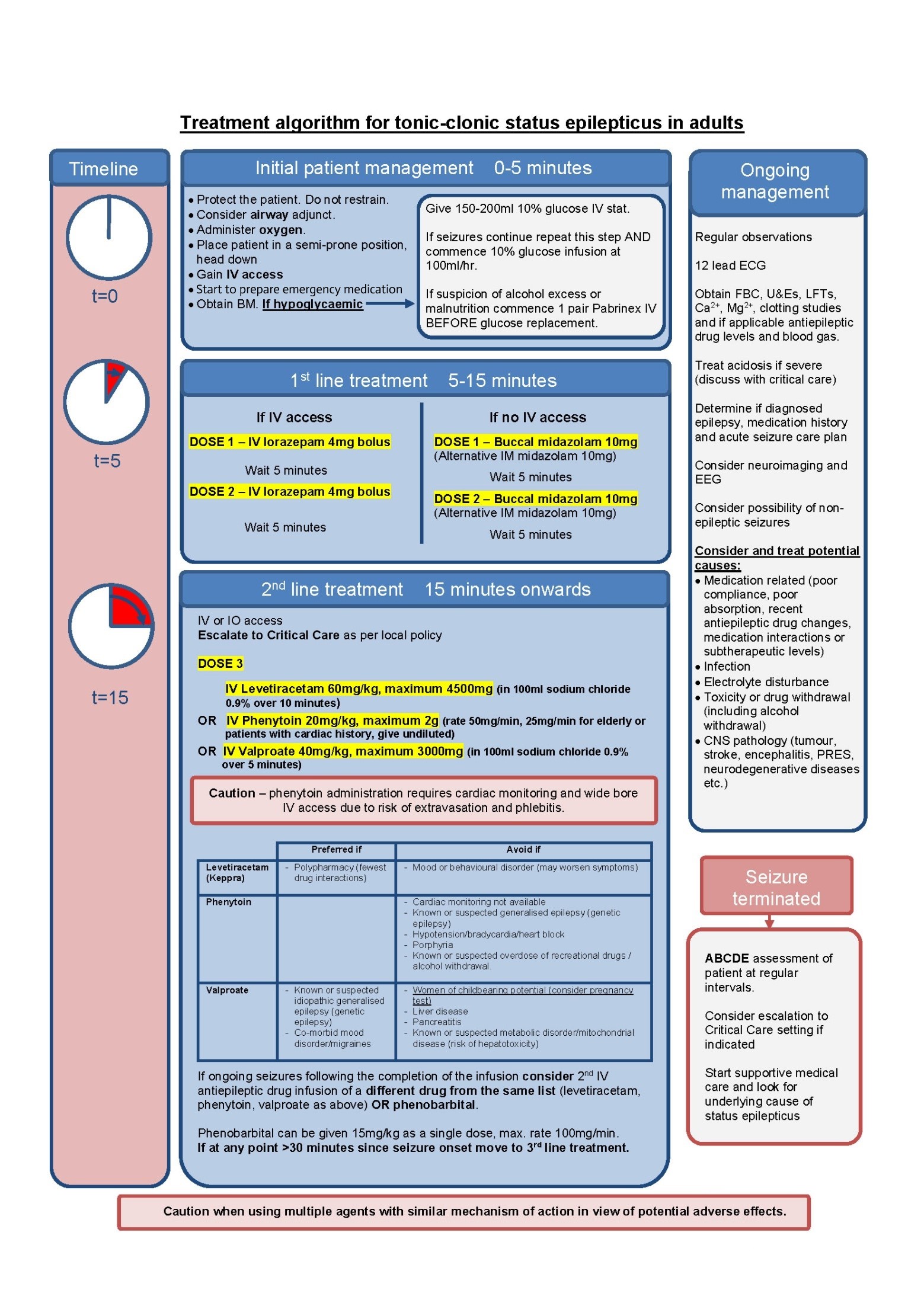

- Updated treatment algorithm/flow chart for initial management of status epilepticus in secondary care

- Inclusion of levetiracetam as a preferred option for second-line therapy after benzodiazepines, with information on loading and maintenance doses (previous guidance was for phenytoin or sodium valproate)

- Expanded prescribing information including useful links

- Treatment of post-cardiac arrest seizures

- More detailed information on second, third and fourth line management options

Status epilepticus is a life-threatening neurological condition defined as five or more minutes of continuous seizure activity or repetitive seizures without regaining consciousness between episodes. On average, 20% of cases are fatal, although studies have reported mortality rates as high as 57% in adults. Most patients have a background of epilepsy, however a number of secondary causes should be considered including stroke, infections, trauma, metabolic disorders, inflammatory conditions, CNS tumours and drug overdose.

Most convulsive seizures terminate spontaneously within three minutes and do not need emergency treatment. After five minutes of continuous seizure activity, the sooner treatment is initiated, the better the chances of seizure termination, and the lower the risk for adverse consequences.

DEFINITIONS AND SCOPE

Status epilepticus can be classified based on a number of clinical features:

- Tonic-clonic status epilepticus (generalised or focal evolving)Paroxysmal or continuous tonic-clonic motor activity that may be symmetrical or asymmetrical with impaired awareness. This variant of status epilepticus is the most common and has the highest associated morbidity and mortality. As a result most of the evidence for treatment interventions has focused on this patient group.

- Focal aware motor status epilepticus

- Motor seizures localised to one side of the body with retained consciousness.

- Status epilepticus without prominent motor symptoms

These include a number of variants: impaired awareness cognitive status epilepticus (coma, obtundation, confusion, disorientation, confusion, disorientation, behavioural disturbance etc.), absence status epilepticus and focal impaired awareness status epilepticus.

THIS GUIDELINE WILL FOCUS ON THE MANAGEMENT OF TONIC-CLONIC STATUS EPILEPTICUS.

The management of patients with focal aware motor status epilepticus OR status epilepticus without prominent motor symptoms (previously referred to as non-convulsive status epilepticus) have a lower risk of morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis and management of such cases can be complex and should be discussed with the neurology consultant or Epilepsy Advanced Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) if consultant unavailable (out of hours contact on call neurology at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary)

TREATMENT OF POST CARDIAC ARREST SEIZURES

The European Resuscitation Council and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine 2021, suggest Levetiracetam or Sodium Valproate as first line to treat post arrest seizures in addition to sedative drugs. In a recently reported trial, valproate, levetiracetam and fosphenytoin were equally effective in terminating status epilepticus but fosphenytoin caused more episodes of hypotension.

PRESCRIBING

All of the medicines used in management of status epilepticus have many side effects, cautions, contraindications and interactions and the prescriber should check BEFORE prescribing.

If a patient is already on epilepsy medication, the patient should have the same brand prescribed each time. This reduces the risk of variation with active ingredients, leading to a further deterioration in seizure control.

For further information please check the following resources:

- https://medusa.wales.nhs.uk

- www.medicinecomplete.com

- www.medicines.org.uk

- https://bnf.nice.org.uk

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Initial Management (t = 0 to 5 minutes)

- Protect the patient. Do not restrain.

- Insert an airway adjunct if safe to do so and administer oxygen.

- Place patient in a semi-prone position with the head down to prevent aspiration, if possible.

- Attempt to establish IV access.

- Determine duration of seizure episode.

- Obtain blood glucose. If the patient is hypoglycaemic give 75mL of 20% glucose immediately. If there is any suspicion of alcohol excess or impaired nutrition commence intravenous infusion of Pabrinex® 1 pair as soon as possible. If patient is hypoglycaemic and still fitting despite first glucose administration repeat IV glucose bolus then start a glucose infusion (10% glucose at 100ml/hr).

- Start to prepare emergency medications.

Whilst continuing with the treatment pathway, the following should be considered but should not delay drug administration:

- Commence regular monitoring of observations (respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, pulse rate, blood pressure and temperature).

- Perform a 12 lead ECG for all patients.

- Check blood glucose, full blood count, renal profile, liver function tests, corrected calcium, magnesium and clotting profile.

- Consider treating acidosis if severe.

- Determine epilepsy and medication history and acute seizure care plan

- Check levels of anti-epileptic medication (where appropriate)

- Consider potential causes:

- Medication related (poor compliance, poor absorption, recent anti-epileptic drug changes, medication interactions or subtherapeutic levels)

- Infection

- Electrolyte disturbance

- Toxicity or drug withdrawal (including alcohol withdrawal)

- CNS pathology (tumour, stroke, encephalitis, PRES, neurodegenerative diseases etc.)

- Organise neuroimaging and EEG where appropriate

- Consider the possibility of non-epileptic seizures.

First Line Drug Treatment (t = 5 minutes)

If seizures persist at 5 minutes, first line benzodiazepine drug therapy should be administered.

If the patient has IV access:

- 4mg of IV lorazepam should be administered (DOSE 1).

- If after a further 5 minutes the seizure has not terminated, a second 4mg of IV lorazepam can be administered (DOSE 2).

In a patient without IV access:

- 10mg of buccal midazolam can be administered (DOSE 1)

- and repeated after 5 minutes if the seizure has not terminated (DOSE 2).

- IM midazolam can be used as an alternative if unable to give buccal midazolam due to trismus.

Dose-dependent depression of consciousness and respiratory drive may result from benzodiazepine administration. This should be considered when monitoring the patient, even once the seizure has terminated.

Up-to a third of cases are resistant to benzodiazepines and will require second line drug therapy. This should commence 5 minutes after DOSE 2 has been administered.

Second Line Drug Treatment (t = 15 minutes)

If seizures continue, IV or IO access must be obtained and the on-call anaesthetist alerted. There is no evidence based preferred second-line drug treatment for status epilepticus, so the drug used should be chosen based on the underlying diagnosis, previous anti-epileptic drug therapy, comorbidity and drug interactions.

The results of the recently published Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) have demonstrated no significant difference in efficacy or adverse events between fosphenytoin, levetiracetam and valproate. (Fosphenytoin is a pro-drug of phenytoin; in NHS Highland the formulary choice is phenytoin and is therefore included in this guideline).

DOSE 3

- IV levetiracetam 60mg/kg, maximum 4500mg in 100ml of sodium chloride 0.9% over 10 minutes

OR

- IV phenytoin 20mg/kg, maximum 2000mg at 50mg/min, reduce rate to 25mg/min in elderly or patients with cardiac disease. Give undiluted with cardiac monitoring (undiluted phenytoin does not require a filter for administration)

OR

- IV sodium valproate 40mg/kg, maximum 3000mg in 100ml of sodium chloride 0.9% over 5 minutes

The varied administration rates of loading should be noted.

For example, in a 70kg patient:

- phenytoin loading would take 28 minutes

- levetiracetam 10 minutes

- and sodium valproate 5 minutes at the above recommended rates.

Please see table below to assist with second-line treatment choices:

|

|

Preferred if: |

Avoid/caution required if: |

|

Levetiracetam |

|

Mood or behavioural disorder (may worsen symptoms) |

|

Phenytoin |

|

|

|

Sodium Valproate |

|

|

Please note that in an emergency situation, the balance of risks and benefits means the prime consideration is to provide optimal and rapid control of the seizures. The above cautions may be more relevant to consider when deciding on long-term maintenance therapy. Patients commenced on anti-epileptic drugs following status epilepticus will be reviewed by the neurology team/ Epilepsy Advanced CNS and treatment may be changed at a later stage if appropriate. Women of childbearing potential who have received a single dose of sodium valproate for the management of status epilepticus should be given advice.

- Phenytoin administration requires cardiac monitoring and should only be given via wide bore intravenous access given the risk of tissue necrosis and extravasation.

- If seizures continue despite completion of the first infusion and when it is also less than 30 minutes since seizure commenced, a second IV anti-epileptic should be considered before anaesthesia. Either a drug from the same list (Levetiracetam, Sodium Valproate, Phenytoin as above) OR Phenobarbital should be used. Phenobarbital can be given 15mg/kg as a single dose, max. rate 100mg/min. It should be avoided in acute porphyria and caution should be taken in the elderly or those at risk of respiratory depression. Consider urgent EEG.

- If at any point more than 30 minutes have elapsed since seizure onset, general anaesthesia should not be delayed and third line drug treatments commenced.

- It should be noted that there is no clear good quality evidence to guide therapy at this stage, and treatment decisions should be guided by senior clinicians with experience in managing refractory status epilepticus.

Third Line Drug Treatment (Refractory Status Epilepticus)

If seizures continue despite second line therapy, the patient is considered to have refractory status epilepticus. Mortality rates are high and as a result rapid initiation of IV anaesthetic agent should be commenced, titrated to suppress epileptic activity on EEG (urgent EEG should be arranged).

The properties of each drug should be considered when selecting induction and maintenance agents.

Note that drugs selected for induction may be different to those chosen for maintenance.

Maintenance doses of anti-epileptic drugs should be continued in addition to the anaesthetic agent. The general anaesthetic agent should be tapered after a minimum of 24 hours and if seizures recur either clinically or electrographically the infusion re-commenced for a further 12 to 24 hours.

Suggested agents:

Propofol

- Induction: 1 to 2mg/kg bolus.

- Maintenance: up to 4mg/kg/hour titrated to effect, continuous infusion for a minimum of 24 hours.

- Propofol has a rapid onset of action. It commonly causes hypotension, and vasopressor support is required in 22 to 55% of patients undergoing infusion. Prolonged infusions can lead to propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS), which is a rare but life threatening complication characterised by metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, hypertriglyceridaemia, refractory bradycardia and cardiac failure. The main risk factors are high infusion rate and infusion duration above 48 hours. Management is supportive, including discontinuation of propofol along with appropriate organ support.

OR

Thiopental sodium

- Induction: 3 to 5mg/kg bolus.

- Maintenance: 3 to 5mg/kg/hour titrated to effect, continuous infusion for a minimum of 24 hours.

- Thiopental is a barbiturate anaesthetic agent with good efficacy and a tendency to lower body temperature which may be beneficial in status epilepticus. Thiopental does, however, have major disadvantages. Firstly, as an infusion it exhibits zero order kinetics and therefore tends to accumulate and have a long half-life. This can lead to an increased duration of ventilator dependency. Secondly, it has potent hypotensive and cardiorespiratory depressive effects, commonly requiring additional vasopressor support. Continuous ECG monitoring should be performed in all patients and senior colleagues involved with treatment decision making.

OR

Ketamine

- Induction: 3mg/kg bolus.

- Maintenance: 1mg/kg/hr titrated to effect up to maximum 10mg/kg/hr, continuous infusion for a minimum of 24 hours.

- There is an increasing body of literature supporting the use of ketamine as a third line agent in the management of refractory status epilepticus, with two randomised controlled trials assessing the efficacy and safety profile of ketamine to conventional anaesthetic agents for refractory status epilepticus currently in progress. Ketamine has a short half-life, reducing the likelihood of toxic accumulation. Compared with other drugs used for the treatment of refractory status epilepticus, respiratory depression and hypotension requiring vasopressor support are rarely observed.

- Note, interpretation of processed EEG monitoring such as bispectral index (BIS) may become unreliable when using ketamine infusion.

OR

Midazolam

- Induction: 0.2mg/kg bolus.

- Maintenance: 0.05 to 0.5mg/kg/hour titrated to effect, continuous infusion for a minimum of 24 hours. Occasionally higher doses up to 50mg/hr may be used on consultant intensivist advice. The rationale for using the doses above 0.5mg/kg/hr need to be documented in case notes.

- Midazolam is short acting, reducing the likelihood of toxic accumulation. Caution should be taken in obese patients due to accumulation in the fat tissues and those with renal insufficiency. It commonly causes hypotension, and vasopressor support is required in 30 to 50% of patients. A number of studies suggest that breakthrough seizures occur more commonly with midazolam compared to other drugs used during this stage.

Fourth Line Drug Treatment (Super Refractory Status Epilepticus)

Super Refractory Status Epilepticus is defined as ongoing or recurring seizures for 24 hours after third line treatment. Treatment at this stage should be guided by specialists using an MDT approach. There is no high quality randomised controlled trial evidence to guide treatment decisions.

- A detailed history should be obtained, and investigations guided by the clinical picture (usually MRI, CSF examination, metabolic screen, drug screen and autoimmune screen). Any underlying cause should be treated.

- Administration and continuation of two anti-epileptic drugs of differing mechanism of action should be considered alongside anaesthetic agents.

- If neuroimaging demonstrates evidence of lesional epileptogenic focus, resective neurosurgery can be considered.

- If no underlying cause is identified and this is a first presentation of seizures, a trial of high dose steroids can be considered. IVIG and therapeutic plasmapheresis can be used if no response despite 2 days of high dose steroids.

Other therapeutic options at this stage include:

- IV Magnesium

- Therapeutic hypothermia

- Ketogenic Diet

- Paraldehyde infusion (particularly if porphyria a possibility)

- Electroconvulsive therapy

When treating outside of recommended dosage and licensing indications it is important to document treatment rationale. Detailed communication with next-of-kin should focus on causes of status epilepticus, treatment decisions and prognosis.

Indications for Intensive Care Admission

Consider admission:

- Seizures continue despite 1st line (benzodiazepine) treatment at recommended dose

- Unstable cardiorespiratory state

- Unstable neurological state

Definite admission:

- Seizures continue despite 2nd line treatments

Ongoing AED treatment

If a patient requires 2nd line treatment, anti-epileptic drugs that have been loaded should be continued at maintenance doses and discussed with neurology, taking into consideration the cautions for individual agents as outlined on page 8. As a general rule for maintenance therapy consider:

- Sodium valproate is contraindicated in pregnancy and in people with childbearing potential

- Phenytoin should not be continued post-discharge

- Levetiracetam should be avoided in patients with actively low mood or anxiety

The first maintenance dose of levetiracetam or sodium valproate should be given as close to 12 hours (10 to 14 hours is acceptable) after the loading dose as is practical, in order to allow regular maintenance dose administration, ideally during daytime hours. The first maintenance intravenous dose of phenytoin should be prescribed 6 to 8 hours after the loading dose.

Suggested doses:

Levetiracetam:

- Continue to prescribe levetiracetam maintenance 1000mg twice daily, unless eGFR<50 ml/min/1.73m2 whereby drug monograph and Renal Drug Database should be consulted. Higher doses as advised by neurology. Wait for 10 to 14 hours after loading dose to prescribe maintenance therapy.

Sodium Valproate:

- Continue IV treatment up to maximum 2.5g daily (unless advised by specialist) in 2 to 4 divided doses by injection over 5 minutes or continuous infusion, usual dose 1000mg twice daily. When switching to oral therapy use the same total daily dose as IV treatment in 2 divided doses.

Phenytoin:

- Initially continue to prescribe phenytoin maintenance 100 mg IV every 6– 8 hours adjusted according to plasma-concentration monitoring. When converting to oral therapy use 3-4 mg/kg/day (usually 150 – 300mg given once daily at night)

For all patients on regular therapy, ensure their usual regular anti-epileptic drugs are prescribed alongside any additional treatment as part of this pathway. It may be necessary to review treatment doses and discuss with a neurologist or Epilepsy Advanced CNS. All patients commenced on new anti-epileptic drugs should be counselled on therapy, including adverse reactions to be aware of and should report to their GP if experiencing. Patients presenting with a first suspected seizure should be given an information sheet (could we link to sheet here?).

A copy of the Immediate Discharge Letter (IDL) should be sent to the Epilepsy Advanced CNS for all patients presenting with status epilepticus/commenced on new anti-epileptic drugs.

Note: some drug recommendations outlined in this guidance are ‘off label’ indications and based on more recent evidence.

- Sculier C, Gaínza-Lein M, Sánchez Fernández I, et al. Long-term outcomes of status epilepticus: A critical assessment. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2018. doi:10.1111/epi.14515

- Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus - Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2015. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-based guideline: Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: Report of the guideline committee of the American epilepsy society. Epilepsy Curr Published Online First: 2016. doi:10.5698/1535- 7597-16.1.48

- Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Marshal Isaacs S, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa002141

- Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2012. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107494

- Barsan W, Cloyd J, Pharm D, et al. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1905795

- Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Emerson RG, et al. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with pentobarbital, propofol, or midazolam: A systematic review. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.28501.

- Singhi S, Murthy A, Singhi P, et al. Continuous midazolam versus diazepam infusion for refractory convulsive status epilepticus. J Child Neurol Published Online First: 2002. doi:10.1177/088307380201700203

- Fernandez A, Lantigua H, Lesch C, et al. High-dose midazolam infusion for refractory status epilepticus. Neurology Published Online First: 2014. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000054

- Marik P. Propofol: Therapeutic Indications and Side-Effects. Curr Pharm Des Published Online First: 2005. doi:10.2174/1381612043382846

- Iyer VN, Hoel R, Rabinstein AA. Propofol infusion syndrome in patients with refractory status epilepticus: An 11-year clinical experience. Crit Care Med Published Online First: 2009. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b08ac7

- Power KN, Flaatten H, Gilhus NE, et al. Propofol treatment in adult refractory status epilepticus. Mortality risk and outcome. Epilepsy Res Published Online First: 2011. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.006

- Rosati A, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Ketamine for Refractory Status Epilepticus: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs. 2018. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0569-6

- Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: A critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011. doi:10.1093/brain/awr215

- Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain Published Online First: 2012. doi:10.1093/brain/aws091

- Hemphill S, McManamin L, Bellamy MC, Hopkins PM. Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.025

- Sculier C, Gaínza-Lein M, Sánchez Fernández I, et al. Long-term outcomes of status epilepticus: A critical assessment. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2018. doi:10.1111/epi.14515

- Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus - Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2015. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-based guideline: Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children and adults: Report of the guideline committee of the American epilepsy society. Epilepsy Curr Published Online First: 2016. doi:10.5698/1535- 7597-16.1.48

- Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Marshal Isaacs S, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa002141

- Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2012. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107494

- Barsan W, Cloyd J, Pharm D, et al. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med Published Online First: 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1905795

- Claassen J, Hirsch LJ, Emerson RG, et al. Treatment of refractory status epilepticus with pentobarbital, propofol, or midazolam: A systematic review. Epilepsia Published Online First: 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.28501.x

- Singhi S, Murthy A, Singhi P, et al. Continuous midazolam versus diazepam infusion for refractory convulsive status epilepticus. J Child Neurol Published Online First: 2002. doi:10.1177/088307380201700203

- Fernandez A, Lantigua H, Lesch C, et al. High-dose midazolam infusion for refractory status epilepticus. Neurology Published Online First: 2014. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000054

- Marik P. Propofol: Therapeutic Indications and Side-Effects. Curr Pharm Des Published Online First: 2005. doi:10.2174/1381612043382846

- Iyer VN, Hoel R, Rabinstein AA. Propofol infusion syndrome in patients with refractory status epilepticus: An 11-year clinical experience. Crit Care Med Published Online First: 2009. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b08ac7

- Power KN, Flaatten H, Gilhus NE, et al. Propofol treatment in adult refractory status epilepticus. Mortality risk and outcome. Epilepsy Res Published Online First: 2011. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.006

- Rosati A, De Masi S, Guerrini R. Ketamine for Refractory Status Epilepticus: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs. 2018. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0569-6

- Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: A critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain. 2011. doi:10.1093/brain/awr215

- Shorvon S, Ferlisi M. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain Published Online First: 2012. doi:10.1093/brain/aws091

- Hemphill S, McManamin L, Bellamy MC, Hopkins PM. Propofol infusion syndrome: a structured literature review and analysis of published case reports. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.12.025

- Nolan JP, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care. Resuscitation. 2021. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care (cprguidelines.eu)

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. Randomized trial of three anticonvulsant medications for status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 2019;381:210313, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMoa1905795.

- SIGN 143. Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults. 2018; SIGN143_Guideline