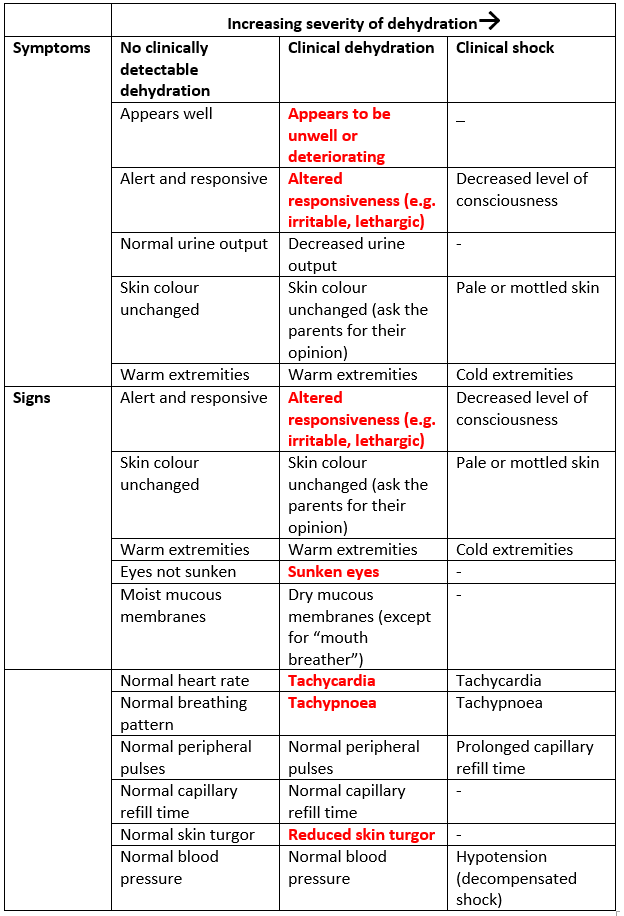

3.1 Management overview

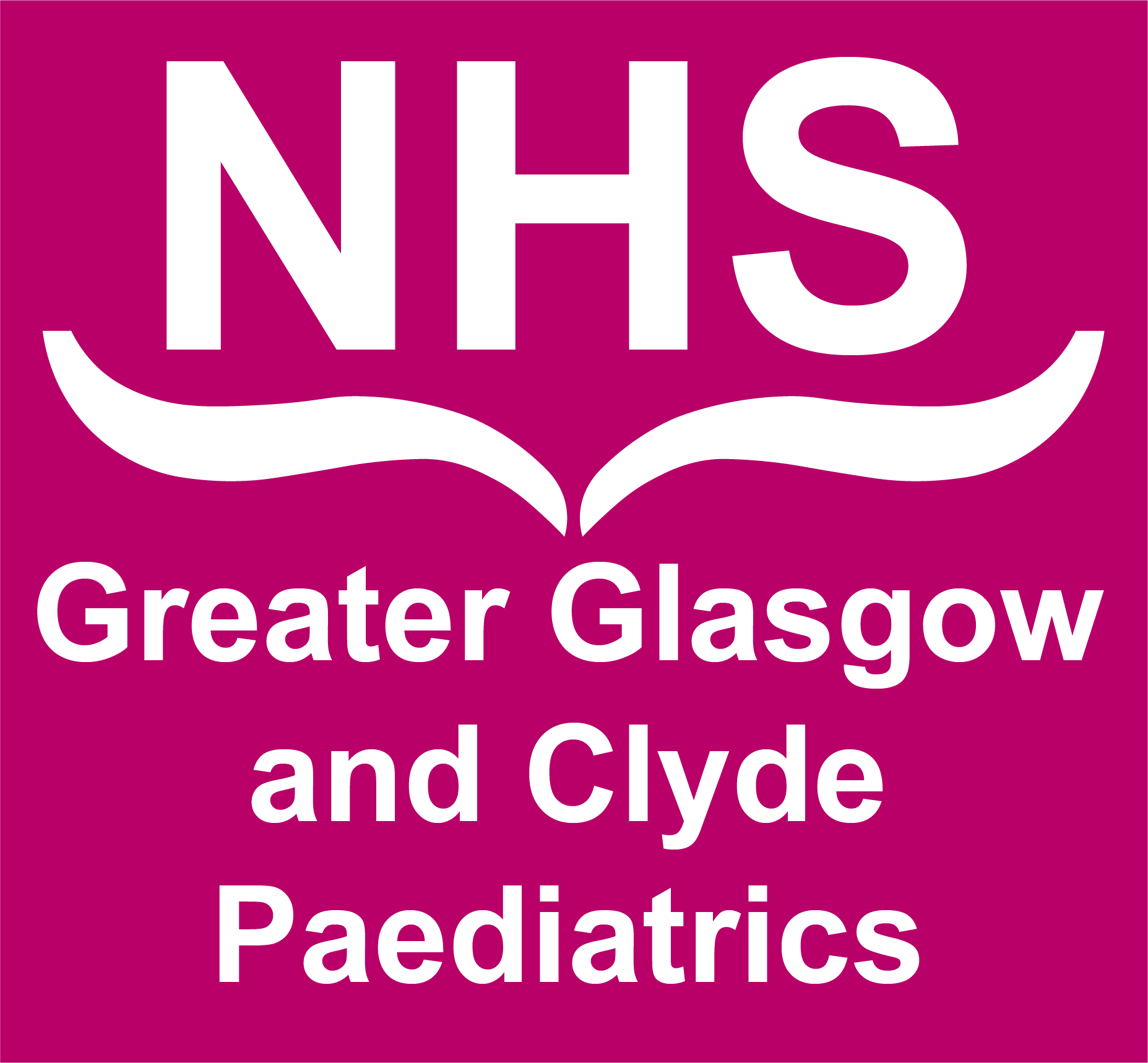

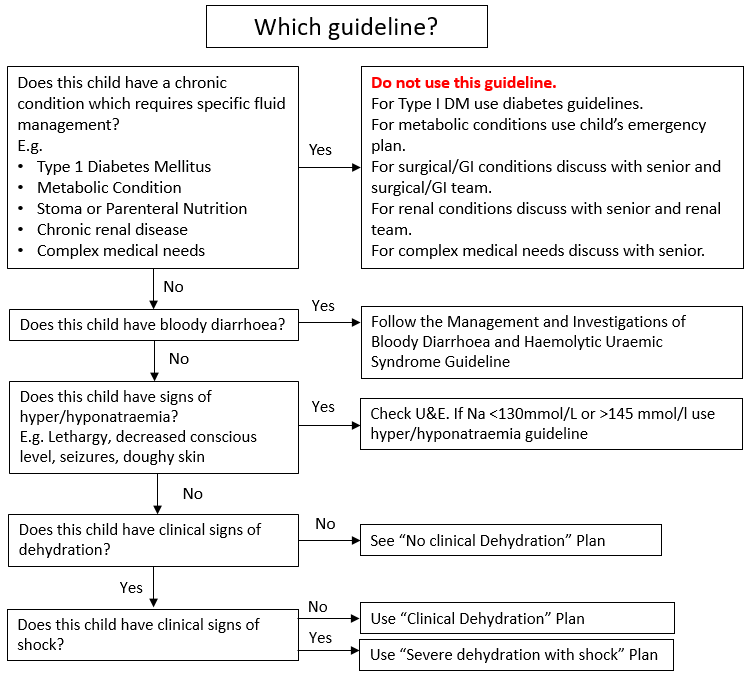

Management approach depends on hydration status, risk factors for dehydration, the presence of bloody stool or hypo/hypernatraemia, and co-morbidities which require special fluid management. To determine the appropriate management approach see Figure 1: Which Guideline.

Note - children with chronic conditions requiring specific fluid management (e.g. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, metabolic conditions, stoma or parenteral nutrition, chronic renal disease, complex medical needs), children with bloody diarrhoea, and children with signs of hypo/hypernatraemia should follow alternative guidelines or individual patient management plans in discussion with a senior doctor (Figure 1).

Management Plans for children with no dehydration, clinical dehydration, and shock are based on WHO guidance for the management of severe dehydration1, with IV fluid management based on NICE guideline NG29 and ESPGHAN Guidelines2,3. For discussion of the basis of IV fluid recommendations see section 3.5.

Figure 1: Choosing an appropriate management approach for gastroenteritis

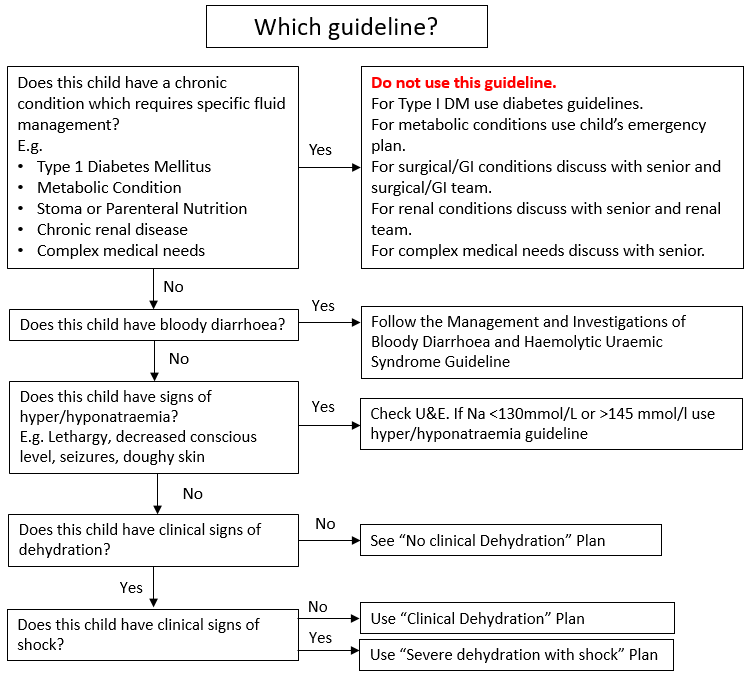

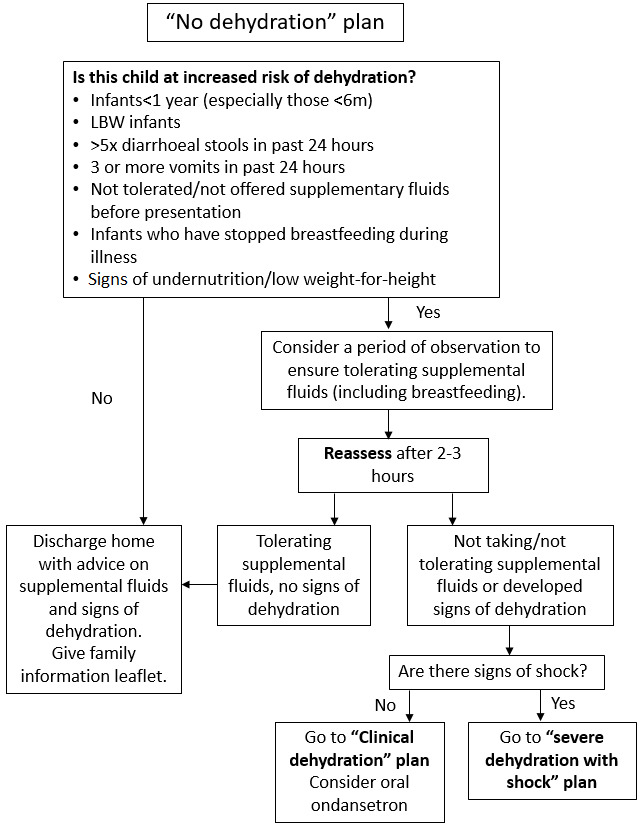

3.2 No Dehydration Plan

Children with no dehydration and no risk factors for dehydration should be managed according to No Dehydration Plan (Figure 2). Assess children for increased risk factors for dehydration and consider a period of observation (Figure 2). Children with no risk factors should be able to be managed within the ED as they can either be discharged, or only require a 2–3-hour period of assessment to assess that they can tolerate oral fluids and do not have ongoing vomiting. If they need to progress to Clinical Dehydration Plan (Figure 3), they should be transferred to CDU. This includes children who are not dehydrated but have not drunk at all in the ED.

Appropriate supplemental fluid advice to be followed at home or in hospital includes:

- continue breastfeeding and other milk feeds

- encourage appropriate fluid intake

- offer dilute apple juice (50% apple juice and 50% water)

- offer oral rehydration solution (ORS) solution as supplemental fluid to those at increased risk of dehydration.

See discharge advice for additional advice for parents

Figure 2: No Dehydration Plan

3.3 Clinical Dehydration Plan

Children with signs and symptoms of clinical dehydration, but no shock, should be managed according to Clinical Dehydration Without Shock Plan (Figure 3). These children should be managed in CDU following initial assessment in ED, since this Plan is likely to take 4 hours to complete.

Figure 3:Clinical dehydration without shock plan

To complete a 50ml/kg volume of ORS over 4 hours target volumes per 5 minutes according to weight may be used (Table 2). If given via nasogastric tube give 50ml/kg over 4 hours (hourly rate = total volume (50ml/kg) ÷4). Ensure continuous NG feeds are stopped after 4 hours and hydration status reviewed.

Table 2: Target volumes of ORS per 5 minutes by weight for children with clinical dehydration

|

Weight (kg)

|

5 min volume of ORS

|

|

0-5

|

5mls

|

|

5-10

|

10 mls

|

|

10-20

|

20 mls

|

|

20-30

|

30 mls

|

|

>30

|

30 mls

|

For children who fail oral rehydration and require IV fluids see additional notes in section 3.5.

For replacement of ongoing stool losses see Section 3.5.4

3.4 Severe Dehydration with Shock Plan

Children with signs of shock should be managed according to Severe Dehydration with Shock Plan (Figure 4). These children should be managed in ED until stabilised. Transfer to CDU or to an in-patient ward following stabilisation should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Shock due to severe dehydration alone is rare in the UK. Consideration should always be given to alternative diagnoses such as sepsis, toxic-shock syndrome, diabetes ketoacidosis, or a surgical cause. Early senior review to confirm hydration status and assess for alternative diagnosis is recommended.

Figure 4: Severe dehydration with shock plan

3.5 Recommendations on IV fluid management for dehydration and replacement of losses

3.5.1 Recommended composition of IV fluids

All the cited guidelines1-4 recommend isotonic fluids for IV management of dehydration and maintenance IV fluids. All guidelines recommend initial resuscitation should be with 0.9% saline, some suggest Ringer’s Lactate as an alternative, but given the limited availability of Ringer’s Lactate in the UK we have recommended 0.9% saline.

However, use of 0.9% saline in high volumes is associated with a risk of hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis and therefore is not first choice for maintenance fluids or ongoing deficit correction.5 The first choice for ongoing maintenance is Plasmalyte, which contains bicarbonate precursors and has a physiologic chloride level and may therefore be more effective at correcting, and not worsening, acidosis.5 Plasmalyte can also be used to replace ongoing stool losses, although 0.9% saline with added potassium chloride can be used as an alternative.

Plasmalyte with 5% dextrose should be given following initial resuscitation. This may avoid hypoglycaemia, particularly in younger children, and aid correction of ketosis. Blood glucose should be monitored 4-6 hourly (more frequently if concerns or in younger children).

3.5.2 Addition of Potassium to IV fluids

Potassium loss in stools or vomiting can be high in gastroenteritis and additional potassium may be required.

The following rules should be followed if additional potassium is required:

- Only use solutions with a total maximum potassium concentration of 20mmol/l. Plasmalyte contains 5mmol/l potassium, therefore 15mmol should be added to make a 20mmol/l concentration. (See IV fluid monograph: adding potassium or dextrose to plasmalyte).

- If 0.9% saline with added potassium is used, ideally use pre-prepared bags. If not, follow IV monographs to add 20mmol/litre.

- If using IV fluids containing 20mmol/l potassium, ensure fluid prescription does not exceed 10ml/kg/hour for children weighing ≤100kg, or 1 litre/hour for young people weighing >100kg. This will ensure the rate of potassium infusion will not exceed the recommended maximum of 0.2mmol/kg/hour (max 20mmol/hour).

- If additional potassium is required, U&E should be checked at 6-12 hourly intervals.

3.5.3 Recommended rate of deficit replacement.

The evidence base for recommended rate of intravenous fluid replacement in dehydration is poor, and older guidelines (including the WHO guidelines and NICE CG84) are largely based on expert opinion/standard practice in low income and high income settings respectively.6 We have chosen to base our recommendations on the ESGHAN/ESPID 2014 guidelines, which reflect emerging evidence in support of more rapid deficit replacement. Where there are gaps in the ESGHAN/ESPID guidance we have taken a pragmatic approach and ensured guidance is in line with other countries such as the US and Canada which use similar rapid replacement strategies. We will update this guideline as further evidence emerges, or if UK guidance is updated.

3.5.4 Ongoing Monitoring

Many clinical errors in the management of gastroenteritis arise from failure to monitor fluid balance. All children admitted with gastroenteritis should be on a strict fluid balance chart with measurement of losses. It is accepted that weighing of nappies containing both stool and urine will overestimate stool losses, but this is preferable to under-estimation. Older children should be instructed to use bedpans so that stools and urine can be measured.

Previous weights (including on iGrow, recent clinic attendances, previous ED attendances) should be reviewed and compared to current weight on admission. For ongoing monitoring of hydration status in hospital all children should be weighed daily. Weight should be recorded on the fluid chart, on HEPMA, in patient notes and on iGrow.

In the first 24 hours of admission fluid balance should be reviewed by medical staff at least 6 hourly and recorded in the medical notes. This should include accurate fluid input and output. Note children will be expected to be in positive balance initially while deficit is being corrected. A negative or neutral balance in this initial phase should prompt consideration of further investigations and replacement of ongoing losses.

Ongoing stool losses can be significant particularly in infants, or in pathogens associated with profuse diarrhoea such as Enterotoxigenic E.Coli (traveller’s diarrhoea). Failure to replace these losses can result in persistent or worsening dehydration in hospital.

Losses should be replaced over 4 hours, either by addition to the total volume of maintenance fluids/hour, or by running a separate infusion to replace losses. There are pros and cons to both approaches. In either case, the prescription of additional fluids should be a separate prescription for no more than 4 hours to ensure regular review. Fluids used for replacement of losses should contain additional potassium (see above), e.g. Plasmalyte.

A positive balance once deficit has been replaced should prompt review of urine output, and hydration status. Children should be encouraged to restart oral fluids as soon as able.

3.6 Drug treatment in the management of gastroenteritis

3.6.1 Ondansetron

While Ondansetron has been shown in some studies to reduce vomiting in children with gastroenteritis and reduce the need for admission/IV fluids, it has also been shown to increase stool losses and potentially increase risk of dehydration.7 There are also concerns about use of ondansetron in children with hypokalaemia due to the risk of Q-T prolongation.8 NICE and ESPGHAN guidelines do not currently recommend the routine use of Ondansetron. A single dose of oral Ondansetron can be considered9 in children who:

- are 6 months or older

- have mild-moderate dehydration or have failed a trial of oral rehydration therapy

- do not have moderate or severe diarrhoea – i.e. have not had >5 diarrhoeal stools in the last 24 hours. If diarrhoea as opposed to vomiting is the main symptom do not give Ondansetron

- have no signs of bowel obstruction or bilious vomiting

There is no benefit to repeat doses of Ondansetron, and further doses may increase the risk of adverse effects.

Ondansetron dosage is 0.15 mg/kg in liquid format (to a maximum dose of 8 mg). Alternatively, a reasonable weight-based oral dosing regimen for infants and children is the following:

- 8 kg to 15 kg: 2 mg

- 15 kg to 30 kg: 4 mg

- Greater than 30 kg: 6 mg to 8 mg

3.6.2 Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not generally indicated in children with gastroenteritis. Antibiotics should be given to children:

- with suspected or confirmed sepsis

- with extra-intestinal spread of bacterial infection

- younger than 6 months with salmonella gastroenteritis

- who have a low weight-for-height or are immunocompromised with salmonella gastroenteritis

- with Clostridium difficile-associated pseudomembranous enterocolitis, giardiasis, dysenteric shigellosis, dysenteric amoebiasis or cholera (discuss with ID team).

Management of these children is beyond the scope of this guideline. All these children should be discussed with the ED or Medical consultant and/or ID consultant.