FND (Functional Neurological Disorder) is one of the most common conditions seen in neurological practice, affecting approximately 10,000 people in Scotland. It can manifest as a range of symptoms including functional seizures, impaired mobility/weakness, speech, and movement disorders.

It is a hidden and stigmatised problem, which often falls between specialities. People with FND experience similar levels of disability to conditions such as Multiple Sclerosis or Epilepsy, and high frequencies of psychological distress.

Services or specialists sometimes ‘exclude’ people with FND, despite increasingly good evidence for the benefits of multidisciplinary assessment and treatment1.

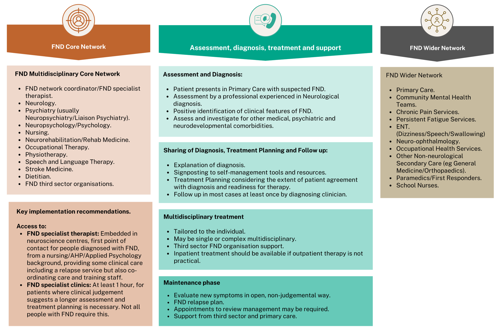

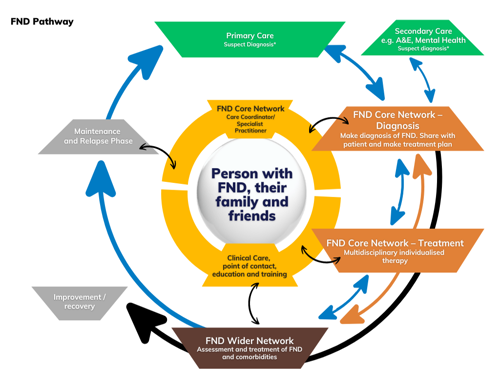

This pathway is based on the most recent systematic reviews of the evidence2–6 7, existing consensus recommendations for therapy8–10, and other relevant pathways11,12, and aims to improve care across Scotland to ensure equity of access for people with FND relative to people with other neurological conditions such as epilepsy and multiple sclerosis who have similar symptoms.

What is FND?

FND in this document refers to:

- Functional limb weakness or paralysis, sensory and speech disturbance

- Functional movement disorders like tremor, dystonia, gait disorder and jerks

- Functional seizures– events that look like epileptic seizures or syncope

- Persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD)

- Functional Cognitive Disorders

- Functional dysphonia, swallowing problems, and hearing problems

- Functional visual problems

What is not FND?

FND should not be used to describe ALL functional symptoms and disorders. It does not, for example include chronic pain/fibromyalgia, persistent fatigue, or functional gastrointestinal problems such as irritable bowel syndrome. Those disorders commonly co-exist in people with FND and may have shared mechanisms.

Who is this pathway for?

This pathway has been created to provide:

Benefits to People with FND:

- Recognition that FND is real, common, and disabling

- Better access to evidence-based treatment for FND

Benefits to Services:

- Recommendations to Health Boards and practitioners on the content of an FND service.

- More efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective use of existing services.