Management is supportive unless there are indications for exchange transfusion. The aim of treatment is to break the cycle of: sickling, hypoxia and acidosis - all exacerbated by dehydration.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT INCLUDES:

- reassurance that the patient’s pain will be relieved as soon as possible

- warmth and establishing a position of maximum comfort

- analgesia

- hydration

- intravenous access if required for fluids, analgesia, antibiotics

- identification and treatment of infection

- regular observations and reassessment

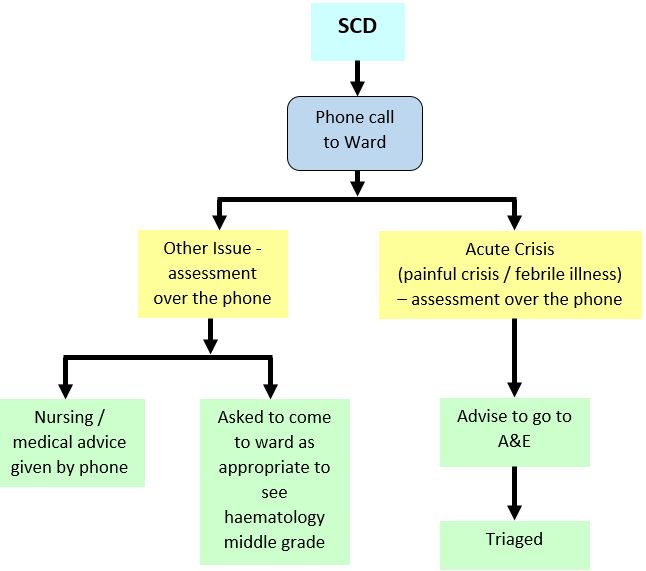

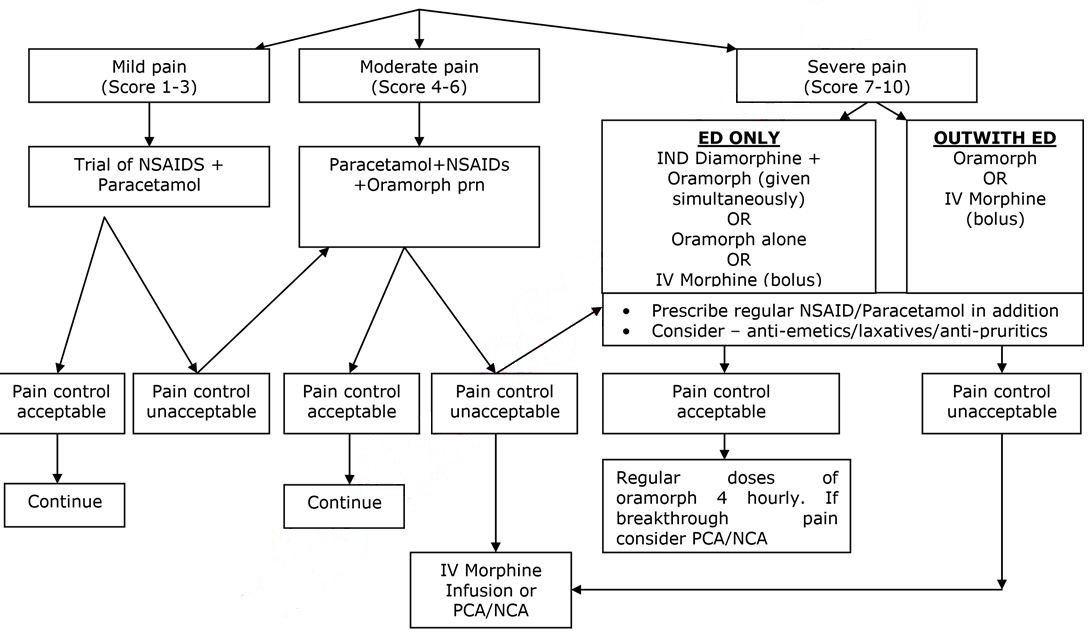

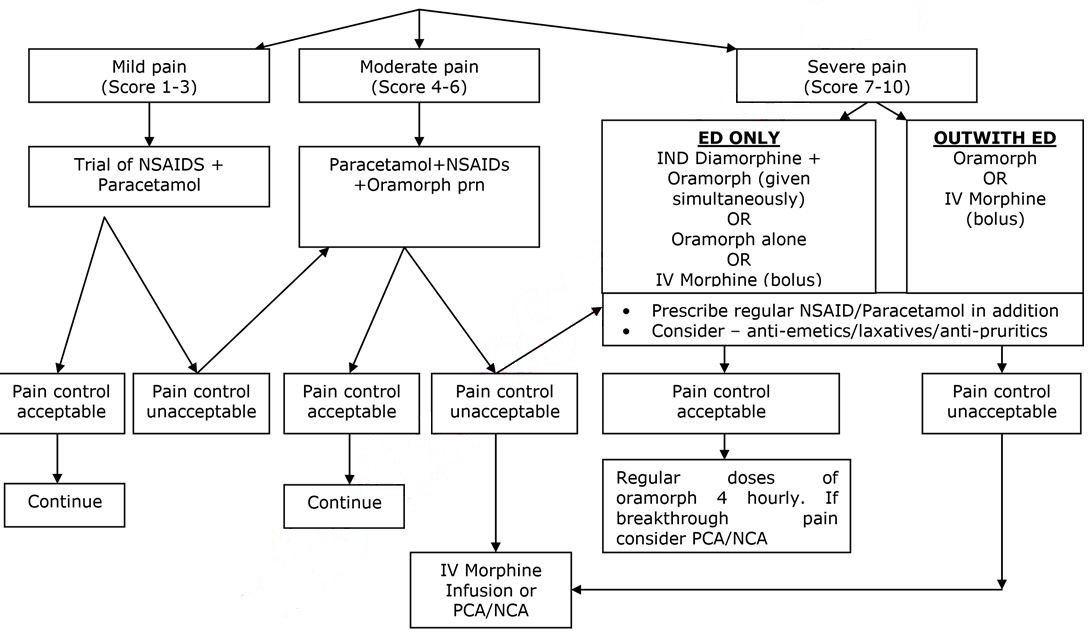

ANALGESIA – SEE FLOW CHART BELOW

- Pain is the commonest cause of hospital admission and needs to be addressed urgently. Analgesia should be administered within 30 minutes of arrival and aim for pain control within 60 minutes.

- Pain in sickle cell disease may be very severe, and is often underestimated by healthcare professionals.

- Assessment should include analgesia taken prior to attending hospital.

- Pain assessment should include the use of an age appropriate pain assessment score, which may be helpful as part of the overall assessment of the patient.

- Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents (NSAIDs) and Paracetamol may have synergistic effects and should be prescribed in addition to opiate analgesia.

Monitoring

The following should be monitored in all patients on analgesia:

- Severity of pain (use validated pain score)

- Sedation level

- Pulse, BP, temperature

- Respiratory rate

- Oxygen saturations in air

These observations should be performed at least every 30 minutes until the pain has been controlled and observations are stable, then according to local pain management protocols, or at least every 2 hours whilst the patient is on opiate analgesia. If the respiratory rate falls below 10/minute then any opiate infusion should be discontinued and consider the use of naloxone.

FIRST DOSE ANALGESIA SHOULD BE ADMINISTERED WITHIN 30 MINUTES

(FOR DOSES OF DRUGS REFER TO INFORMATION BELOW)

SEVERE PAIN

Intra nasal Diamorphine (IND) – if patient presents in ED –see below:

(For full guideline refer to Pain in children, management in the ED- “Guideline for using Intra nasal Diamorphine” 2015: Author Joanne Stirling).

It should be noted that IND and 1st dose of Oramorph should be given simultaneously. If IND contraindicated/unavailable, Oramorph or IV morphine should continue to be administered as per protocol.

Guideline for using Intranasal Diamorphine (to be used in conjunction with Emergency Department Pain Management Guideline)

Indications:

To be included as part of the first-line treatment of severe pain in a child (without IV access). For example, in children with pain secondary to:

- Clinically suspected limb fractures

- Painful/distressing burns

Contraindications:

- Need for immediate IV access (use parenteral morphine)

- Significant nasal trauma

- Blocked nose or upper respiratory tract infection

- Age < 1 year (or weight <10kg)

- General contraindications/sensitivity to diamorphine or morphine use

- Significant head injury

Protocol:

- Weigh the child in kg, transfer to resuscitation area (if not already done), monitor O2 sats

- Prescribe diamorphine via intranasal route (in mg) based on child’s weight (see chart – round to nearest weight; final dose=0.1mg/kg) and use chart (below) to determine the volume of water to add to a 5mg diamorphine ampoule. Mix well.

- Draw up 0.2 mls (0.1mg/kg) of the resultant solution into a 1ml syringe and discard the rest (following controlled drugs procedure).

- Gently tip child’s head and instil 0.1ml into each nostril (total of 0.2mls in drops). Occlude the other nostril after each 0.1ml and ask the child to sniff.

- Don’t forget to give supplementary oral analgesia (if not contra-indicated) and that the child may need ongoing IV analgesia once the initial pain is controlled.

- Intranasal diamorphine is usually effective within 5-10 minutes but allow up to 20 minutes for maximal pain control.

- Continue O2 sats monitoring for 1 hour post administration. Analgesic effect lasts up to 4 hours. Providing the child is stable, they can be transferred elsewhere within the department for ongoing monitoring once diamorphine has been administered.

Guideline for making up Intranasal Diamorphine Solution

Dilute 5mg of diamorphine powder with specific volume of sterile water

|

Weight (kg)

|

Volume of sterile water to be added |

Final dose in mg (in 0.2mls) |

|

10

|

1ml |

1mg |

|

11

|

0.9ml |

1.11mg |

|

12

|

0.85ml |

1.18mg |

|

14

|

0.7ml |

1.43mg |

|

16

|

0.6ml |

1.67mg |

|

18

|

0.55ml |

1.82mg |

|

20

|

0.5ml |

2mg |

|

25

|

0.4ml |

2.5mg |

|

30

|

0.35ml |

2.86mg |

|

35

|

0.3ml |

3.33mg |

|

40

|

0.25ml |

4mg |

|

≥50

|

0.2ml |

5mg |

Oral morphine:

|

From

|

From

|

Dose

|

|

1 months

|

2 months

|

50 - 100 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

|

3 months

|

5 months

|

100 - 150 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

|

6 months

|

11 months

|

200 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

|

1 years

|

1 years

|

200 - 300 micrograms/kg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

|

2 years

|

11 years

|

200 - 300 micrograms/kg (maximum 10mg) every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

|

12 years

|

17 years

|

Initially 5-10mg every 4 hours, adjusted according to response

|

StatIV bolus of morphine (if required) once access established. This will take 5-20 minutes to take effect. Dose should be given by titration over at least 5 minutes to assess efficacy of dose.

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

1 year

|

18 years

|

100 micrograms/kg/dose (max 5mg initially)

|

When pain control is established consider continuous infusion. Refer to the Pain Team during working hours or to the Anaesthetist on call if out of hours for assessment.

Pain Relief Nurse Specialist: ext 84319/84320

Duty Anaesthetist: ext 84342/84842

Pain Consultant or on call consultant: check rota via switchboard or via extension 84316

Follow the Acute Pain Relief Protocol (APRS) V20 (Sep 2019)

NOTE: the decision to start a continuous infusion of an opioid or ketamine, or to modify doses and treatment remains with the Pain Team/Anaesthetists. The guidelines below have been included in this protocol to help with important information on safe monitoring of patients in the Ward who are managed with these drugs. Continuous follow up by the Pain Team/Anaesthetists for routine assessments and for advice on managing potential complications is required.

Efficacy of analgesia should be assessed repeatedly over the first few hours and adjusted if necessary. Patients will vary in their analgesic requirements.

Opioid Infusions:

Morphine sulphate is the first line opioid used in RHC, Glasgow. Oxycodone is the second line of opioid choice in RHC, Glasgow. However, Oxycodone can be considered as first line opioid choice in patients with Sickle Cell Disease who in previous admissions have experienced side effects to Morphine or better pain control with Oxycodone.

Intravenous Morphine/Oxycodone Infusion:

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula.

Morphine/Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(≡0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls

|

Initial IV Morphine / Oxycodone settings for paediatrics

|

|

Self-ventilating

Age :>3m: up to 0.020mg/kg/h ie. 20micrograms/kg/h ≡ 1ml/hr

Ventilated in intensive care

Up to 0.04mg/kg/h ie. 40micrograms/kg/h ≡ 2ml/hr |

Patient controlled Analgesia with Morphine / Oxycodone (PCA)

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula. However if the patient has PCA Accufuser, 6 hourly 0.9% N.Saline flushes should be prescribed to ensure patency on IV cannula.

Morphine / Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(º0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls (1mg/ml)

|

Initial IV PCA settings

|

|

Bolus dose 0.020mg/kg ie. 20micrograms/kg ≡ 1.0ml. Maximum bolus dose 1mg (for 50kg+)

Lockout interval 5 minutes

Background infusion 0.004mg/kg/hr ie.4micrograms/kg/h ≡ 0.2ml/hr

[useful in first 24h to improve sleep pattern] Omit if 50kg+ or if has had single shot epidural or regional block

|

Nurse controlled Analgesia with Morphine / Oxycodone (NCA)

Dedicated anti-syphon/reflux infusion lines with maintenance fluids to ensure patency of cannula.

Morphine /Oxycodone syringe should be prepared as 1mg/kg in 50mls 0.9%saline

(≡0.02mg/kg/ml ie.20micrograms/kg/ml); maximum 50mg in 50mls (1mg/ml)

|

Initial NCA settings

|

|

Age > 3m self-ventilating, or child of any age ventilated in intensive care

Bolus dose 0.020mg/kg ie. 20micrograms/kg ≡ 1.0ml

maximum bolus dose 1mg (for 50kg+)

Lockout interval 20 minutes

Background infusion 0.020mg/kg/h ie.20micrograms/kg/h ≡ 1ml/h

|

KETAMINE INFUSION - This should only be undertaken by anaesthetists or trained pain management nurse specialist - if a trainee, discuss with your consultant and the pain team.

Minimum monitoring standard for patients - MAJOR analgesic techniques:

- Patients should be centrally monitored when on wards

- Use of DECT phones is required.

- One nurse per 4 patients.

- Continuous pulse-oximetry.

- Hourly pain assessment and nurse recordings using the appropriate chart which are available in clinical areas.

- Regular visits by pain relief nurse specialist and/or duty anaesthetists

Minimum monitoring standard for patients ALL OTHER analgesic techniques:

- Four hourly pain assessments should be carried out on the PEWS charts.

General points:

- Doses are a guide only and should be titrated with monitoring. The medical condition, surgical condition, age and maturity of the child should be taken into account.

- Any member of nursing or medical staff who have had appropriate training can perform refilling of opioid syringe.

- All children with epidural infusions, nerve infusions, NCA and PCA should have accompanying IV fluids for the duration of time the technique is running. However if the patient has PCA Accufuser, 6 hourly 0.9% N.Saline flushes should be prescribed to ensure patency on IV cannula

- Programming or reprogramming of PCA/NCA devices or epidural pumps should only be performed by the APRS and appropriately trained staff.

- Ensure all syringes, bags and lines for opioid or local anaesthetic infusions are correctly labelled.

- Ensure prescription is correctly and legibly written, signed, dated and timed on the additive label, in the drug Kardex/HEPMA and on the monitoring/prescription chart.

- Ensure the appropriate monitoring/prescription chart has all the requested information accurately completed, and accompanies the patient to the ward or unit.

- If in PICU, duplication of signs/recordings on the APRS chart is not required but fields not recorded on the PICU electronic record should be completed on the paper chart.

Beware!

All opioid and local anaesthetic infusions should be checked and signed by 2 practitioners.

Double check

- Drug dosages.

- Drug dilutions.

- Pump settings.

- Concurrent prescription of different opioids,

- All PCA/NCA must have an antisyphon line to prevent siphoning and reflux of opioid.

- Ensure opioid and epidural pumps not >20cm above patients head to prevent gravity free flow of infusion.

- Ensure obvious labelling of local anaesthetic infusions to avoid misconnections.

Injection or infusion of the wrong substances into epidurals or iv cannulae can be fatal.

Antagonists:

- Use Basic Life Support measures (ABC); give oxygen

For morphine antagonism:

|

|

Naloxone dose

|

|

Excess sedation but SaO2>94% air

Responds to pain stimulus

|

2micrograms/kg iv stat;

can be repeated every 60 seconds

|

|

Excess sedation & SaO2 <94% in air

Responds to pain stimulus

|

10micrograms/kg iv stat

|

|

Unresponsive

|

20micrograms/kg iv stat

|

Start an infusion, if required, at 10micrograms/kg/hr; use lowest effective dose:

|

For benzodiazepine antagonism:

Flumazenil 5 micrograms/kg iv stat;

Can be repeated every 60 seconds or start infusion at 10 micrograms/kg/hr

Beware seizures precipitated by antagonists

|

Moderate Pain:

- Oral Morphine (Oramorph) – see above for doses

- Oral Codeine – not used in RHC Glasgow

Mild Pain:

Oral Paracetamol:

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

Neonate (32 weeks corrected gestational age and above

|

20 mg/kg for 1 dose, then 10-15 mg/kg every 6 – 8 hours as required. Maximum daily dose to be given in divided doses (maximum 60mg/kg per day)

|

|

1 month

|

2 months

|

30-60 mg every 8 hours as required. Maximum daily dose to be given in divided doses (maximum 60mg/kg per day)

|

|

3 months

|

5 months

|

60 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

6 months

|

1 year

|

120 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

2 years

|

3 years

|

180 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

4 years

|

5 years

|

240 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

6 years

|

7 years

|

240 - 250 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

8 years

|

9 years

|

360 - 375 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

10 years

|

11 years

|

480 – 500 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

12 years

|

15 years

|

480 – 750 mg every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

|

16 years

|

17 years

|

0.5 – 1 g every 4 - 6 hours as required. Maximum 4 doses per day

|

Oral Ibuprofen:

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

1 months

|

2 months

|

5mg/kg 3-4 times daily

|

|

3 months

|

5 months

|

50mg 3 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

6 months

|

11 months

|

50mg 3 - 4 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

1 years

|

3 years

|

100mg 3 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

4 years

|

6 years

|

150mg 3 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

7 years

|

9 years

|

200mg 3 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg to a maximum of 2.4g daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

10 years

|

11 years

|

300mg 3 times daily

(maximum 30mg/kg to a maximum of 2.4g daily in 3 – 4 divided doses

|

|

12 years

|

17 years

|

300 - 400mg 3 - 4 times daily

|

Fluids

Dehydration occurs readily in children with sickle cell disease due to impairment of renal concentrating ability and may aggravate to sickling due to increased blood viscosity. Diarrhoea and vomiting are thus of particular concern. Patients may also have cardiac or respiratory compromise and so fluid overload must also be avoided.

Careful assessment of individual fluid status, administration of an appropriate hydration regimen and close monitoring of fluid balance is therefore imperative.

The ill child should be assessed for the degree of dehydration by the history; the duration of the illness; by clinical examination; and (if known) weight loss. Hb and PCV (Hct) may be elevated as compared with the child's steady state values. These children normally have a low urea and so slight elevation is significant.

An IV line should be established whenever parenteral opiates have been given, or if the patient is not taking oral fluids well. In the less ill patient who is able to drink the required amount, hydration can be given orally. As an alternative consider a nasogastric tube in an alert patient.

IV hydration should be commenced on admission at maintenance rates or appropriate to individual fluid status. A fluid chart should be started and kept carefully, both input and output. Fluid balance must be reviewed regularly (at least 12 hourly) to correct dehydration and avoid fluid overload. Check urea and electrolytes at least daily and add KCl as required.

IV therapy can be stopped once the patient is stable and pain is controlled with documentation of adequate oral intake.

Calculation for Hyperhydration:

NOTE: only prescribe HYPERhydration if there is obvious clinical and laboratorial evidence of dehydration associated with the painful episode; if in doubt, prescribe MAINTENANCE IV fluid rates to begin with; if HYPERhydration prescribed, reassess fluid balance frequently and consider reducing fluids to MAINTENANCE rates whenever possible (usually within the first 24-48h).

|

Body weight (kg)

|

Fluids (ml/kg/day)

|

|

First 10 kg

|

150

|

|

11- 20 kg

|

75

|

|

subsequent kilograms over 20

|

30

|

For example: An 8kg infant will require 150 x 8 = 1200ml per 24hrs (50ml/hr) A 16kg child will require (150 x 10) + (75 x 6) = 1950ml per 24hrs (81ml/hr) A 36 kg child will require (150 x 10) + (75 x 10) + (30 x16) = 2730ml/24hrs (114ml/hr)

Electrolytes should be reviewed, remembering that a slightly raised urea will be significant as these children normally have a low blood urea.

- Check urea and U+Es at least daily and add KCl as required.

Oxygen

This is of doubtful use if the patient has only limb pain, but may be given if requested by the patient. The patient’s oxygen saturation (SaO2) should be monitored by pulse oximetry with regular readings in air (minimum 4 hourly).

- If SaO2< 95% in air, give O2 by face mask.

- Check capillary or arterial gases if SaO2in air is <90%.

- Monitor SaO2 while patient is on supplementary O2, aiming to keep SaO2> 98%.

- Inform consultant if deteriorating respiratory condition and consult acute chest syndrome protocol.

Physiotherapy

Children with Sickle Cell Disease should be referred for chest physiotherapy on admission if they:

- Have Acute Chest Syndrome

- Have had previous Acute Chest Syndrome

- Require IV opiate analgesia

- Are admitted for surgery (ie: splenectomy, abdominal surgery)

- Have back, chest, rib or abdominal pain

- Have X-ray changes

- Have clinical signs of infection

- Have decreased mobility

WORKING HOURS - Mon-Fri 09:00-17:00 - Contact the Respiratory Physio team by telephone in the first instance (ext: 84802, 08:30-16:30) and complete a Trakcare referral.

OUT OF HOURS – at present there is no access to routine Incentive Spirometry out of hours. Children with Sickle Cell Disease who have been admitted out of hours, are not critically unwell and fulfil any of the above criteria for referral, should be referred to Physiotherapy (by completion of a Trakcare referral) and await Physiotherapy assessment the next working day. Critically unwell children with Sickle Cell Disease and chest signs should be referred and discussed with the Respiratory Physio on call on admission.

The SPAH network have published guidelines on Physiotherapy assessment and referral pathways.

Antibiotics

Infection is a common precipitating factor of painful or other types of sickle crises. These children are immunocompromised. Functional asplenia or hyposplenia occurs, irrespective of spleen size, resulting in an increased susceptibility to infection, in particular with capsulated organisms such as pneumococcus, neisseria, Haemophilus influenzae and salmonella – all of which can cause life-threatening sepsis.

- In uncomplicated painful crisis without specific evidence of infection increase prophylactic Phenoxymethylpenicillin (Penicillin V) to 4 times per day after cultures (blood, urine and any other source that is indicated) have been taken.

- If penicillin allergic, use erythromycin 4 times per day.

- Any unwell child with sequestration syndrome, chest syndrome or obviously toxic should receive intravenous antibiotics as per local antibiotic policy. Mild to moderately unwell children with a temperature of >38.0 should also receive intravenous Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (or according to local antibiotic policy) after appropriate cultures have been taken.

- Dosing regimen: Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (90mg/kg/dose 4 times a day)

- If there are chest signs, or an abnormal CXR, give Piperacillin Tazabactam (Tazocin) (IV) and clarithromycin (IV or oral) or Azithromycin (oral).

- If symptoms/signs of focal infection are present (eg tonsillitis, UTI), treat appropriately according to local microbiological advice.

- If penicillin allergic with a reaction classified as non-serious, use Ceftazidime (IV).

- If penicillin allergic with a reaction classified as serious (serious allergy is one that causes an anaphylactic or urticarial reaction, 10% of patients with reactions to penicillin-based antibiotics will also have a reaction with cephalosporins) use erythromycin (IV) or clarithromycin (IV) +/-ciprofloxacin.

- Patients on desferrioxamine (DFO) who have diarrhoea should be started on ciprofloxacin immediately (after checking they are not G6PD deficient) and the DFO stopped. Ciprofloxacin can be stopped if Yersinia infection has been excluded. Siblings of children with Salmonella infections should be discussed with the microbiology team.

Other Drugs

Please prescribe:

a) Folic Acid (oral)

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

Birth

|

1 month

|

0.5mg once daily

|

|

1 month

|

12 years

|

2.5mg once daily

|

|

12 years

|

18 years

|

5mg once daily

|

b) Anti-emetic: eg Cyclizine (if required with opiate analgesia)

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

1 month

|

6 years

|

0.5-1.0 mg/kg 3 times daily

|

|

6 years

|

12 years

|

25 mg 3 times daily

|

|

12 years

|

18 years

|

50 mg 3 times daily

|

c)Laxatives, if receiving opiate analgesia e.g. Lactulose, Senna, Macrogols – doses adjusted according to response

Lactulose:

|

From

|

To

|

Starting Dose

|

|

1 month

|

1 year

|

2.5 mls 12 hourly

|

|

1 year

|

5 years

|

5 mls 12 hourly

|

|

5 years

|

10 years

|

10 mls 12 hourly

|

|

over 12 years

|

|

15 mls 12 hourly

|

Senokot liquid (5mls= 7.5mg):

|

From

|

To

|

Starting Dose

|

|

1 month

|

2 years

|

0.5ml/kg/dose at night

|

|

2 years

|

6 years

|

2.5-5mls at night

|

|

6 years

|

12 years

|

5-10 mls at night

|

|

over 12 years

|

|

10-20 mls at night

|

d) Macrogols:

|

From

|

To

|

Dose (adjust to response)

|

Product

|

|

1 month

|

1 year

|

1/2 – 1 sachet

|

Laxido Paediatric

|

|

1 year

|

6 years

|

1 sachet

|

Laxido Paediatric

|

|

6 years

|

12 years

|

2 sachets

|

Laxido Paediatric

|

|

12 years

|

adult

|

1 – 3 sachets

|

Laxido

|

e) Antipruritic (if receiving opiate analgesia)

Oral Chlorphenamine Maleate (Piriton):

|

From

|

To

|

Dose

|

|

1 month

|

2 years

|

1 mg twice daily

|

|

2 years

|

5 years

|

1 mg 4-6 hourly

|

|

6 years

|

12 years

|

2mg 4-6 hourly

|

|

12 years

|

adult

|

4 mg 4-6 hourly

|

Consider non-sedating antihistamines if sedated with Piriton

f) Iron chelation therapy – e.g. Desferrioxamine (if they would receive this normally)

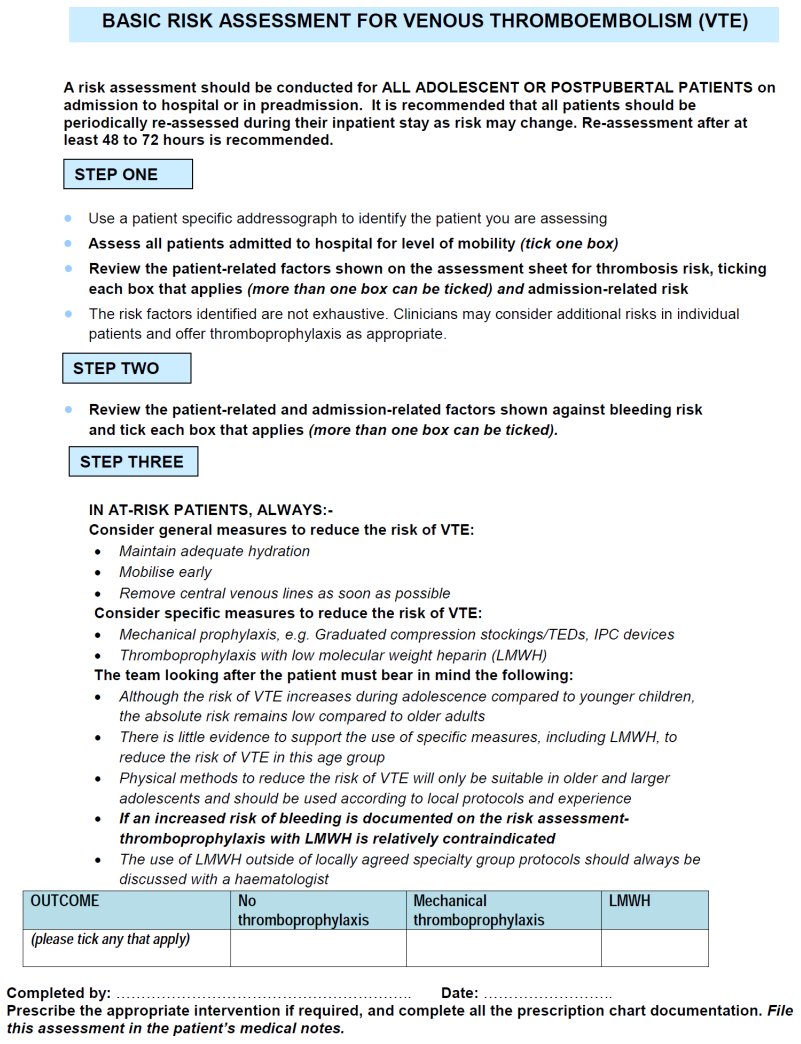

g) Thromboprophylaxis - LMWH (Clexane): consider in those ≥13yrs of age.

Please refer to Appendix 1 and also Section 5.10 of the Anti-thrombotic protocol (HAEM-007).