3.1 Goals of HFOV

3.2 Terminology

3.3 Mechanisms of Lung Injury

3.4 Conventional ventilation vs HFOV: Fundamental Differences

3.5 Mechanism of Gas Transport in HFOV

3.6 Determinants of gas exchange in HFOV

3.7 Optimal Ventilation Strategy

3.8 Nasal HFOV

3.1 Goals of HFOV

- To achieve and maintain optimal lung inflation

- To use the lowest Fi02

- To ensure optimal gas exchange while minimising the risk of ventilator induced lung injury

3.2 Terminology

Mean Airway Pressure - a continuous distending pressure measured in cm H20

Amplitude/D P - the peak to trough measure of the pressure waveform. This is the measure of pressure the ventilator uses to push air into the circuit. ΔP (amplitude) creates the wiggle seen in HFOV.

Frequency - the rate at which oscillations are delivered. Expressed in hertz where 1 hertz = 60 breaths per minute

Functional Residual Capacity - the volume of air present in the lungs at the end of expiration

Dead Space - the air in the nose, mouth, larynx, trachea, bronchi and bronchioles where air does not come into contact with the alveoli of the lungs i.e. the portion of tidal volume that does not take part in gas exchange

3.3 Mechanisms of Lung Injury

Theories of of ventilator induced lung injury:

Volutrauma

The use of large tidal volumes to achieve adequate ventilation damages the pulmonary capillary endothelium, alveolar and airway epithelium. This mechanical damage causes fluid, protein, and blood to leak into the airways, alveoli and interstitial tissue of the lung and leads to progressive respiratory failure.

Atelectotrauma

Refers to the damage caused to a lung unit by repetitive opening and closing of the alveoli. This opening, collapse and reopening of alveoli causes surface forces which have the potential to damage the surface epithelium of the airways.

Barotrauma

Mechanical damage caused to the airways by the application of high positive airway pressures

Oxygen toxicity

The administration of excessive levels of oxygen and the action of oxygen free radicals is implicated in lung disease and in the development of retinopathy of prematurity. Un-scavenged oxygen free radicals have a direct effect on pulmonary epithelial cells leading to cell membrane injury. The lungs, in response to this damage tries to regenerate but the repair is fibrotic, which is typical of chronic lung disease in premature infants.

3.4 Conventional ventilation vs HFOV: Fundamental Differences

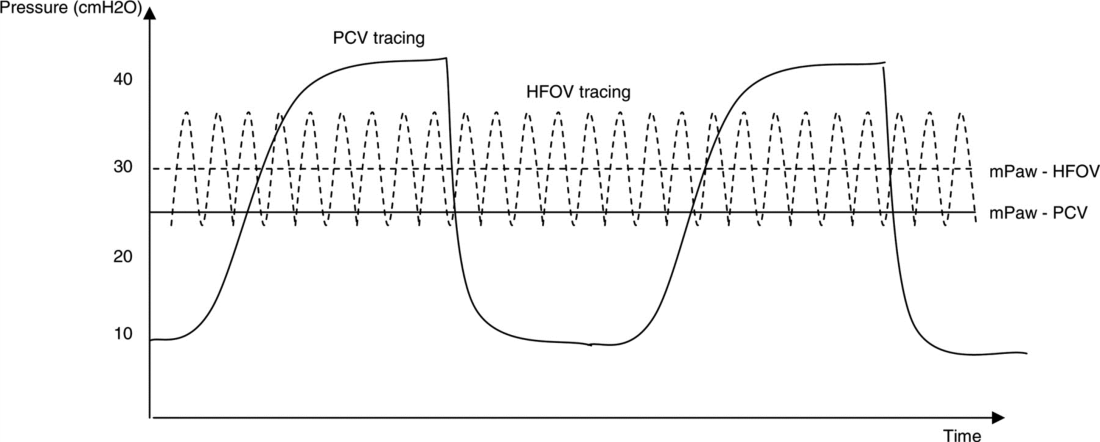

HFOV involves applying a pressure waveform over a continuous distending pressure. In most ventilators both the inspiratory and expiratory cycles are active i.e. gas is pushed in and pulled out. An alternative means of creating oscillation is by flow interruption.

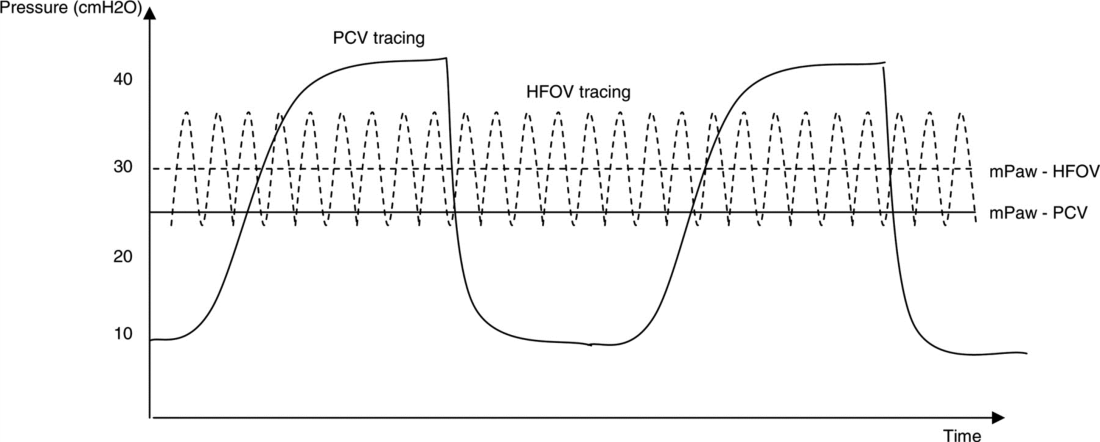

During HFOV alveoli are kept open utilising a continuous distending pressure (the mean airway pressure: MAP) and not subjected to large pressure and volume swings causing the traumatic ‘inflate-deflate’ cycle to maintain gas exchange (Figure 1). In contrast during conventional ventilation the alveoli open and close on every breath delivered and large pressure swings (PIP/PEEP) are required to move relatively large volumes of gas to enable adequate gas exchange to occur.

Figure 1: Ventilation waveform in Conventional ventilation (PCV = Pressure Controlled Ventilation) and HFOV.

(Reproduced from Chan KP, Stewart TE, Mehta S. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation for adult patients with ARDS. Chest. 2007; 131(6):1907-1916.)

In HFOV oxygenation is decoupled from ventilation and each can be controlled independently. Oxygenation is determined by inspired FiO2 and lung recruitment, which is determined by MAP. Carbon dioxide clearance (i.e. ventilation) is controlled separately by the tidal volume which is dependent on oscillation frequency (oscillations per minute) and amplitude of the waveform ΔP (amplitude).

As per the Cochrane review (2015), there is evidence that the use of elective HFOV compared with CV results in a small reduction in the risk of CLD, but the evidence is weakened by the inconsistency of this effect across trials. Probably many factors, both related to the intervention itself as well as to the individual patient, interact in complex ways. In addition, the benefit could be counteracted by an increased risk of acute air leak. Adverse effects on short-term neurological outcomes have been observed in some studies but these effects are not significant overall. Most trials reporting long-term outcome have not identified any difference.

3.5 Mechanism of Gas Transport in HFOV

Gas transport in HFOV is thought to be complex and accomplished by a combination of the following mechanisms (see also Figure 2):

- Direct alveolar ventilation – ventilation by bulk flow to proximal lung units

- Pendelluft effect – The transfer of gas between lung units with different time constants i.e. transfer of gas from rapidly filling alveoli to slower filling alveoli

- Convective streaming – the shape of the stream of gas caused by rapid movement of gas forming an arrow shaped gas flow which penetrates the dead space

- Augmented (Taylor) dispersion - In the lungs, the branching network of the airways together with Pendelluft movement, leads to gas turbulence and mixing between the core and the periphery of the gas column and radial dispersion is eliminated. This results in greater gas mixing with lower tidal volumes.

- Cardiogenic mixing – the mixing of gas facilitated by the turbulence created in the airways by the pumping action of the cardiac muscle

- Molecular diffusion – the process by which molecules spread from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration.

Figure 2: Proposed mechanisms of gas transport in HFOV

(Reproduced from Slutsky, AS, Drazen, JM Ventilation with small tidal volumes.N Engl J Med2002; 347,630-631)

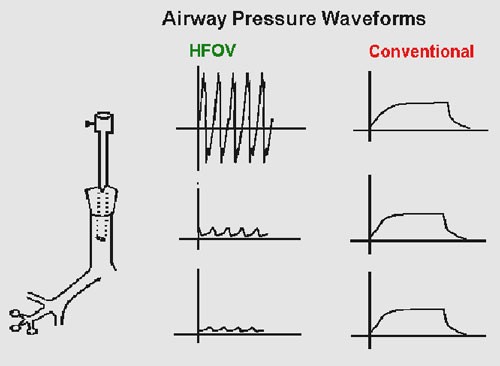

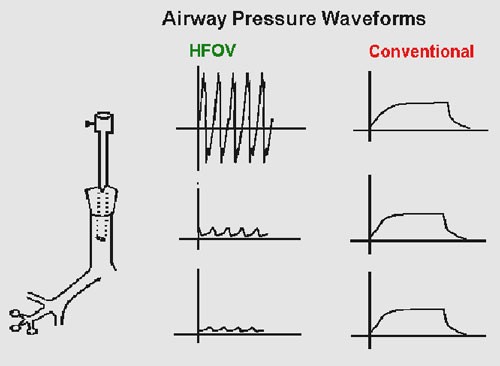

It is important to appreciate that in HFOV the pressures set at the ventilator and delivered at the ET tube are not the same as those reaching the alveoli. Approximately 10% of the ΔP (amplitude) delivered at the endotracheal tube is transmitted to the terminal bronchioles and alveoli, compared with 90% of PIP transmission during conventional ventilation (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Reduction in HFOV waveform along respiratory tree

(Reproduced from Rajiv P K .Essentials of Neonatal Ventilation 2010)

3.6 Determinants of gas exchange in HFOV

The determinants of oxygenation and CO2 clearance (ventilation) during HFOV are discussed in detail below and summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Ventilation parameters and effect on oxygenation and ventilation in HFOV and conventional ventilation (CMV)

(Reproduced from Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne Newborn Services Guidelines – 2014)

Determinants of oxygenation in HFOV

Oxygenation is determined by lung volume and oxygen concentration delivered (FiO2). The mean airway pressure (MAP) setting on the HFOV is used to modify lung volume by recruiting atelectatic lung units and optimising the alveolar surface area for gas exchange. The MAP is considered to act as a continuous distending pressure (CDP) on the alveoli. The goal of recruitment manoeuvers in HFOV is to open atelectatic lung units to gas exchange and then find the lowest possible mean airway pressure to keep them open (see Optimal ventilation strategy below)

Determinants of ventilation (CO2 clearance) in HFOV

In conventional ventilation modes CO2 clearance is determined by minute ventilation which is: minute volume tidal volume x frequency. The HFOV equivalent of minute volume is the gas transport coefficient or DCO2.

During HFOV CO2 clearance is determined by the amplitude (ΔP) (amplitude) and frequency (measured in hertz):

- Amplitude (DP): The amplitude is created by the distance that the piston/diaphragm moves and is the peak to trough swing (oscillation) around the mean airway pressure. The movement created by this swing results in a gas volume displacement and a visual chest wiggle. The higher the ΔP (amplitude), the greater the displacement of gas i.e. tidal volume. An increase in DP (amplitude) should result in an increased tidal volume and increased removal of CO2.

- Frequency: Frequency is the number of cycles per minute: one hertz equals 60 cycles per minute. Decreasing hertz results in increased time for the oscillatory wave form cycle to be delivered thereby increasing tidal volume and improving CO2 Decreasing hertz will also result in less attenuation of the oscillatory waveform, generating more chest wall movement and increasing CO2 removal. This is in contrast to conventional ventilation where increases in rate cause increased tidal volumes and enhanced CO2 removal.

3.7 Optimal Ventilation Strategy

Successful application of HFOV is dependent upon ventilation with the lung recruited, known as the open lung strategy or the high lung volume strategy.

Continuous distending pressure (MAP) during HFOV recruits the lung if sufficient pressure is applied on initiation to open most lung units and retains volume if sufficient pressure is maintained to keep most lung units open. In other words, the goal of the open lung strategy is to open collapsed alveoli to gas exchange and then find the lowest possible MAP that will keep them open.

The ‘art’ of HFOV relates to achieving and maintaining optimal lung inflation. Optimal oxygenation is achieved by gradual increments in MAP to recruit lung volume and monitoring the effects on arterial oxygenation. The aim is to achieve maximum alveolar recruitment without causing over-distension of the lungs.

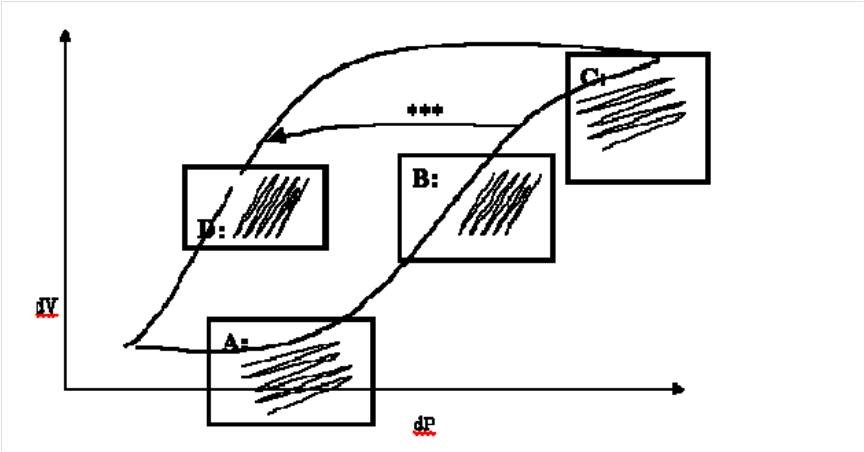

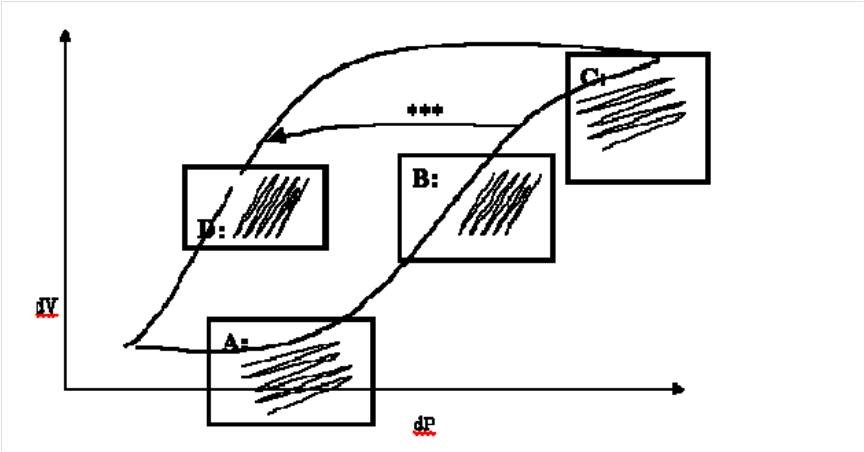

Optimising lung inflation with MAP: It is useful to conceptualise HFOV as like taking the lung around one sustained pressure volume hysteresis loop (Figure 5). Using the principles of P/V relationship, lung recruitment and and optimal range of lung volume we can apply these to optimise lung volume and oxygenation (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Pressure volume relationship in the lung demonstrating optimal pressure range with maximal lung recruitment (lung volume)

(Reproduced from Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne Newborn Services Guidelines – 2014)

Figure 6: Pressure volume relationship in the lung demonstrating different stages of lung inflations as detailed below as Point A,B,C and D

(Reproduced from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney Newborn Services Guidelines – 2006)

Point A in figure: Under-inflation: At this point the lung is under-inflated, PVR will be high and relatively large amplitude will produce only small changes in volume. Clinically this manifests as a high oxygen requirement with limited chest vibration. CO2 clearance is also reduced.

Point B in figure: Optimal recruitment inflation: Once the lung has opened up with higher MAP, smaller amplitude will produce a larger change in volume. Clinically this manifests as improved oxygenation (falling oxygen requirements) and good chest vibration resulting in improved CO2 clearance. PVR will also be lower.

Point C in figure: Over-inflation: At this point excessive MAP has produced over-inflated lung. Oxygenation and CO2 clearance will start to deteriorate and PVR will increase contributing to cardiovascular compromise. This is the most dangerous point in HFOV and is to be avoided at all costs. It is difficult to pick clinically because the oxygen requirement may stay low, although they will eventually rise and the reduced chest vibration is easy to miss. Chest X-ray may be helpful to detect over-inflation.

Point D in figure: Optimal inflation: The goal should be to move the babies lungs from point B to point D avoiding point C (as shown on the arrow marked *** in Figure 2). Having achieved optimal lung inflation by slowly reducing MAP it should be possible to maintain the same lung inflation, oxygenation and ventilation at a lower MAP. If MAP is lowered too far oxygen requirements will start to rise again

Optimising ventilation:

- This is controlled mainly by adjusting amplitude (ΔP) to achieve optimal pCO2. Although the amplitude (ΔP) of each breath appears large by comparison to conventional ventilation pressures, the attenuation of oscillation through the endotracheal tube (ETT) means that the transmitted amplitude at the level of the alveolus is very small.

- Higher amplitude (ΔP) will increase tidal volume and hence CO2 removal.

- With increasing ventilator frequency, lung impedance and airway resistance increases so the tidal volume delivered to the alveoli decreases further. This contributes to the apparent paradox that increasing ventilator frequency may reduce CO2 elimination, leading to raised PaCO2 and vice-versa.

3.8 Nasal HFOV

Nasal HFOV (NHFOV) is a non-conventional technique through an external non-invasive interface. Although NHFOV is being used in Europe, US, and other countries there is not much experience in using it in UK.

It combines the benefits of distending nasal CPAP pressure with the active ventilation of HFOV, and removes CO2 without the need of synchronization. In NHFOV, settings are similar to invasive HFOV, and parameters need serial adjustments according to patients’ monitoring. Also, the ‘lung recruitment’ strategy can be performed in the same manner as invasive HFOV.

In NHFOV, gas exchange is influenced by the tidal volume and the small oscillatory volume by the cyclic pressure oscillations delivered all along the respiratory cycle. These oscillations may be variably transmitted along the respiratory tree depending on the lung pathology, patient position, size and type of interface. Therefore, outcome could be different in different patients. The reported adverse effects include abdominal distention and increased upper airway secretions, which could be attributed to usage of low frequencies with high amplitude.

In a multi-centre trial in preterm infants (mean GA 29.4 weeks) by Zhu et al. (2022) reported a slightly reduced duration on invasive ventilation post-extubation and until discharge when started on NHFOV, as compared to nCPAP and NIPPV. It was also associated with less use of postnatal steroids and better weight gain. A secondary analysis of a randomized control trial (2023) found nasal HFOV and NIPPV to be equally effective reducing the duration of invasive ventilation when compared with nasal CPAP. There is need of adequately powered RCTs in the extreme preterm population to see if nasal HFOV is superior to other available NIV modes when used for primary or post-extubation NIV.